The Ford Escort RS Cosworth was probably the world’s first Yob Car, the White Lightning-swilling, shellsuit-wearing, foul-mouthed star of every Jeremy Kyle show you’ve ever seen. With parents that disowned it and a public that held it responsible for all of the nineties’ ills, it was the unloved bastard-child that a disenfranchised generation took to its heart. Jeremy Clarkson bought one (of course he did, were a car and man ever more perfectly suited?) but it bested even him: “Late at night, when all I wanted to do was to get home, it would be sitting there, angry and spoiling for a fight.”

The early years

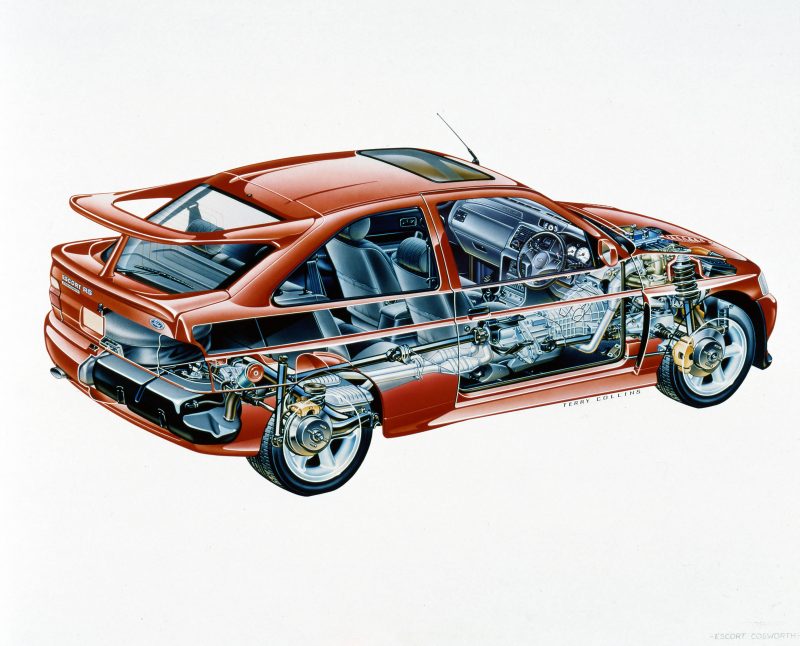

Despite the engineering bodgery[1], the Escort Cosworth went quite well. The two-litre, twin-cam, turbocharged Cosworth engine churned out 227bhp and 220lb/ft of torque, enough to see 60mph off in 6.3 seconds on the way to a top speed of 138mph.

This was heady stuff in 1992, even if the lag from the Garrett T3/T04 turbo was so bad that Jeremy Clarkson, at that time possibly the Escort Cosworth’s biggest fan, said the turbocharger “worked in geological time.”

Two trim levels were available: the Club-spec car was aimed at the motorsport enthusiast that was going to rip most of the trim out anyway, while the Lux version added Recaro seats, electric windows and mirrors, central locking, a heated rear screen and a sunroof. The two cars differed slightly in their performance as a result: Club-sport cars could hit 60mph in 5.7 seconds while the Lux cars needed an extra 0.4 seconds, weighed down as they were by all that frippery.

But the secret sauce, the magic behind the badge, was a four-wheel-drive system that split the torque 34/66 front-to-rear. This, and the finely honed suspension, endowed the Escort Cosworth with incredible agility and poise, no matter what the weather or road surface. The Escort Cossie was as lithe as a freshly shaved stoat and just as angry; it changed direction on a sixpence partly because it was the first production car in the world to develop downforce at both the front and back.

[1] I’m joking, obviously. I would never say or do anything to upset the Essex Boys.

The conception

By the late eighties the Sierra Cosworth was hopelessly outclassed as a Group A rally tool, a state of affairs that Ford couldn’t possibly accept. So it took the easy route and slipped a three-door Escort bodyshell on top of a Sierra Cosworth’s running gear.

Frank Stephenson, the chap behind cars like the McLaren P1, Maserati MC12, Quattroporte, and GranTurismo MC Stradale, and Ferrari F430 and 612 Scaglietti, originally wanted to plonk a mahoosive triple rear spoiler on the boot lid. This, hilariously, makes the resulting twin rear spoiler an act of leave-it-Frank-it-ain’t-worth-it-mate act of pragmatic self-restraint.

Dear God, the nineties were a wonderful time to be alive.

The lads then cracked out the angle grinder again and cut a couple of holes in the bonnet to channel some more air into the intercooler and then pissed off for an early pint. I’m not sure what day of the week spawned the Escort Cosworth but I’m pretty sure it was the Friday of a bank holiday weekend.[1]

Designed in Essex and built in Germany, the guys at gals at Boreham always knew that the Escort Cosworth was always going to be special. How can we tell? Simple; they gave it the project name ‘Ace’.

[1] I’m being a bit harsh because the only panel that the Escort Cosworth shares with the standard car is the roof.

Coming of age

By May 1994 Ford had built the 2,500 cars that were required to homologate the Cossie and were finally free to do something about the appalling turbo lag. A smaller Garrett T25 turbo might have seen the power drop to 217bhp but in-gear flexibility and overall drivability were vastly improved.

A facelift in 1995 saw the ‘Scort gaining a new honeycomb grille, restyled bumpers, different wheels, and a new dashboard fascia. The wonderful rear spoiler was a delete option by now, as owners desperately tried to disguise their Cosworth as just one of the millions of more mundane Escorts that littered the roads and driveways of middle England.

The Escort Cosworth died in 1996 after 7,145 had been built. Killed by increasingly restrictive emissions legislation few mourned its passing (especially the insurance industry). The Cosworth was dead, but no one cared because no one was buying it then; Ford had firmly turned its back and it’s hard to imagine there was anything other than a sense of relief among the blue oval bigwigs who were tired of being blamed for all of society’s ills.

The filth

Because the early nineties marked a time when there was an explosion of car thefts, primarily for joy riding and ram raiding. The reason was that the super-quick, super-desirable cars we all fell in love with were also super-easy to break into and steal.

The world’s engineering excellence (and there was a lot of that in the late eighties and early nineties) had been devoted to performance rather than crime prevention; an anti-theft deterrent was a door lock, not an immobilizer.

We’ve already seen that some police forces were refusing to chase the Vauxhall Lotus Carlton but others grew a big, fat, hairy pair and bought their own weapons-grade pursuit cars. Some plumped for the Mitsubishi Lancer Evolution or the Subaru Impreza Turbo, while others opted to stick with the trusty blue oval, sitting their finest drivers behind the wheel of a Sierra Cosworth.

Others chose the Escort Cosworth on the basis that you might as well enjoy your work. Those officers lucky enough to be thrown the keys to one hung their titanium balls in the wind and dared the local yoof to come out and play. Most declined, wisely deciding to skulk quietly away and spend their evenings interfering with their Pit Bull terrier or whatever it is that disaffected young men did with themselves while the rest of us got on with trying to earn enough money to actually buy – and insure – a car.

Competition

The Escort Cosworth made its competition debut in 1993 and it proved its worth immediately, winning five of the World Rally Championship rounds and taking the overall title in its first season.

The Cossie continued its winning streak in 1994 but Ford was getting bored by then and handed over responsibility for the works cars to the RAS Sport Team. The Cosworth’s success continued throughout 1995 with both RAS Sport and privateers taking scores of class wins but by 1996 Ford realised that it had made a mistake in outsourcing the cars and took them back in-house. However, changes to the regulations had eroded the Cosworth’s dominance and 1997 saw the introduction of the Escort World Rally Car.

Oh, and it took to the Formula One circuit for two races in 1992 as part of the trials for the then-new concept of a safety car. It performed like a boss, and safety cars were officially introduced the following year.

What’ll she do, mister?

My introduction to the Escort Cosworth came courtesy of Ford’s heritage fleet, the manager of whom was daft enough to lend me one to have a play in. Nor was it any old Cossie; it was the very car that the development team used to sign off the whole project. It was Ground Zero. The Dawn of Creation. It was Genesis.

It was also quite yellow. The custard paintwork never made it onto the options list, which was a small mercy. The Cossie has presence, that’s obvious, but it’s hard to take any car seriously when it is this yellow.

The period feel and looks continue inside; the Recaro seats were purple and I quickly discovered that you sit on them, not in them, so headroom is limited. It reminds me (again) that the two things that distinguish every 80s and 90s car I’ve driven in the past few years are poor brakes and sod-all head- and legroom for the driver.

Of course, the first thing you do when you’ve got the keys to an Escort Cosworth in your hand is to gape at that mahoosive rear wing. Then you take a photograph of it, taking ages to find the angle that demonstrates it best. Then you edit it, and write something pithy and funny and then post it across social media. Then you have to keep stopping doing whatever it is you’re doing to react to all the comments it generates and to thank people for the R/Ts and shares. Only then can you actually drive the bloody thing.

You know I mentioned the turbo lag? Well, Clarkson was wrong. It’s not glacial. It’s far, far worse than that. Still, once you’ve got the old girl wound up she fairly flies but you’ve got to work at it and work hard. And then you remember that 227bhp isn’t that much anymore, so you readjust your expectations to a more appropriate level because the Cosworth doesn’t feel very fast at all. It is an icon of the early nineties, not the 21st century.

This low-mileage car handles and goes as well as they ever did and while the performance isn’t as astonishing as it would have been twenty-odd years ago, there’s enough there to give you a glimpse of how special it was, back in the day. The need to keep it on the boil is foiled not only by turbo lag but by a woolly, obstructive and imprecise gear change. Are the ratios you need are in there, somewhere, but finding the appropriate one couldn’t ever be classed as fun.

The steering though is exactly as you hope it will be, meaty but not overly heavy, and deadly accurate. Understeer is there by the bucketful but late braking and a bit of ragging mid-bend sharpens things up no end. Part of the problem is that the springing and damping is way, way softer than they’d get away with fitting now and the brakes are on the marginal side of barely acceptable, but it’s still got it. Oh boy, has it still got it. You might not be able to think it through the bends but if you get a bit hot ‘n’ heavy and throw it through you’re going to have a lot of fun. Grip levels are high even with those relatively narrow, high-walled tyres and traction is never going to be a worry. It’s more comfortable than its reputation would have you believe, too.

Legends can’t be judged by the standards of today – anything even half-decent would kick it into the middle of next week, much less the Ford Focus RS that I drove there and back – but there’s enough competence to raise an enormous amount of respect. Would I buy one? Probably not; for me the Lotus Carlton would be a better place to put this sort of money but I do get it, and it’s on my Top Ten, that’s for sure.

Buyers’ guide

You’ll want to be certain that any Escort Cosworth you are looking at is, in fact, an Escort Cosworth. That means taking a look at the VIN number (there are two: one is under the bonnet and one under a flap next to the driver’s seat) to check that the chassis number starts with WFOBBXGKABNG followed by a string of five numbers.

After authenticity, the main problems are rust and accident damage, with the latter being more of a problem than the former. A lot of people crashed their Escort Cosworth (mind you, a lot more people crashed other people’s Cosworths; no car has ever captured the imagination of the joy rider like the ‘Scort Cossie did) and repairing them properly is an expensive, long-winded business (it really was a hand-built car) and not everyone did it as diligently as they should have done.

The early cars, by which I mean the first 2,500, suffered from turbo problems as well as lag. The telltale is white smoke on start up, so try not to get too excited and distracted and do pay attention when the owner first starts the engine.

Tuning and tweaking

Tuners found that 300bhp was easily achieved with 400-500bhp being available for relatively small sums. Large sums, and a willingness to sacrifice some reliability, liberated up to 1,000bhp, although many of the cars that boast four-figure bhp might not pass a Jeremy Kyle Show lie detector test…

OE clutches are said to be good for 300bhp and the five-speed gearbox is good for 375bhp, so you’ll need to budget for extensive chassis and transmission work if you aim any higher.

The majority of the cars on sale today will have been modified to one extent or another, and while I wouldn’t be put off too much if the work had been done by someone that knew what they were doing, anything that deviates from standard will affect the value. And not in a good way.

Prices

Unexceptional cars sell for £25,000 with exceptional ones reaching four times that amount. That’s strong money but any fast Ford is selling for strong money these days. I’m not an investment consultant, and my advice is worth exactly what you paid for it, but I can’t see prices dropping anytime soon.

I’d have thought spending between £25,000 and £50,000 on a good ‘un should be as safe as money in the bank. (You know, the bank that pays you 0.25 per cent interest. If you’re lucky…)

Carlton Boyce