The E30 M3 was the first purpose-built BMW racing car to be engineered and assembled in-house by its Motorsport Division. And while most first projects are more about dipping a tentative toe in the water than first-time victory, the fact that the E30 M3 ended its career as the most successful touring car of all time is proof positive that BMW’s advertising strapline ‘The Ultimate Driving Machine’ isn’t necessarily over-hyped marketing tosh.

IN THE BEGINNING

The E30 M3 lasted just six short years, but what a period it was. Launched onto an unsuspecting world in 1986, the M3 only made it onto public roads because the Group A regulations of the time insisted on 5,000 being built as proof that the cars in that class were genuine production models rather than highly-modified homologation specials.

And it had all the good stuff from the get go: 200bhp might not seem like much now, but back then the double-ton was The Holy Grail, an output that LJK Setright described as being enough, yet not too much. (As well as being the absolute maximum that could be transmitted through the wheels of a front-wheel-drive car, but that’s another story for another day.) It was also beautifully balanced, featured a rear-wheel-drive chassis, and was so visually understated as to make its eventual performance all the more of a shock to an unsuspecting M3 virgin.

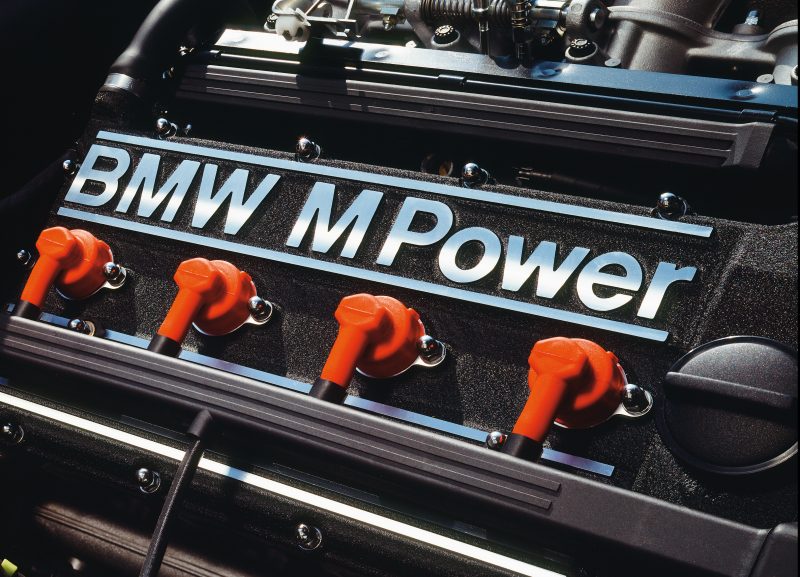

Just the fourth car to wear an ‘M’ badge (only the M1, M635CSi and the M535i preceded it) the M3’s four-cylinder ‘S14’ engine – a direct decedent of the elderly ‘M10’ engine that even saw use in the Brabham-BMW BT52 Formula One car – earned its place under the bonnet thanks to its light weight and ability to rev more highly than the better-balanced but more fragile six-cylinder that might have been a more natural fit under the lid of a high-performance, and very expensive, sporting saloon.

That it was a coarser engine than the inline-six was immediately forgiven the first time you drove it; with a rev limit of 7,300rpm, the 2.3-litre, 16-valve engine might have been tractable enough to trundle to the shops but it still delivered enough of a punch as to enable even the clumsiest driver make the most of that extraordinary chassis.

The dog-leg, five-speed, close-ratio Getrag gearbox, with first gear all the way down and to the left, simply added to the M3 legend, as did the standard limited slip differential, lowered springs, re-valved and uprated Boge dampers, increased negative camber and castor, and thicker anti-roll bars. Oh, and new 15-inch BBS alloy wheels fitted with 205/55VR15 tyres, bigger discs and calipers plus the stronger hub assembly from the 5-series helped too. Simple, obvious stuff, for sure, but it was simple, obvious stuff done properly.

This ethos, of doing the job properly no matter how much it cost or how involved the engineering, was applied to the bodywork too, which might look remarkably similar to the cooking 3-series but was actually very different. The bonnet and doors were stock, and while fitting flared wheelarches to cover the wider tyres was an obvious move, a more steeply raked rear screen and a boot lid that sits 1.5 inches higher than the normal car’s in the name of better aerodynamics probably wouldn’t have been considered an essential modification in the hands of a lesser manufacturer. And, best of all, even with those bigger boots and all the extra aero appendages, the co-efficient of drag actually dropped, from 0.38 to 0.33 Cd.

And, as might be expected given the amount invested in it, the M3 was a success from day one – and a showroom price tag of £22,750, or almost £45,000 today, now seems like a bit of a bargain, even if it was about 25 percent more than the BMW 325i at the time.

Two hundred bhp became 215bhp in 1989, even though a catalytic convertor was by then standard (the earlier catalyst-equipped cars had 195bhp against the non-equipped cars’ 200bhp), and Boge Electronic Damper Control for the suspension had been made available a year before that with three settings on offer: Komfort (K), Normal (N), and Sport (S), all controlled via a very cool knob on the centre console.

But, there was more to come. Much more, because the same Group A regulations that demanded an initial production run of 5,000 also gave provision for the cars to evolve, and the ‘Evolution’ models made even the extraordinary M3 seem rather, well, normal.

THE EVOLUTION

The BMW M3 Evolution 1 might have stuck with the standard car’s 200bhp engine but it did feature a revised cylinder head, mainly to help the tunability of the competition cars. Just 500 were built, all of which fall within the VIN range 2190283-2190787, which is useful information to have because there were no distinguishing badges on the cars to differentiate them from the standard M3, although the front and rear spoilers were unique to the model.

The Evolution 2 of March 1988 boasted 220bhp, a useful increase thanks to changes to the Bosch engine management system, new pistons, a lighter flywheel and a more efficient air intake tract. It also featured bigger wheels and tyres – 7.5×16” and 225/45ZR16 respectively – and a lower final drive ratio on the otherwise unaltered Getrag gearbox.

The bodywork received the attentions of the development team too, and you can spot one by its deeper front spoiler and air ducts in place of the standard M3’s front fog lights. The rear spoiler was changed too, but thinner glass and a lighter boot lid and bumpers were less obvious. Three new colours – Misano Red, Nogaro Silver, and Macao Blue – were offered, and a dashboard plaque was fitted so your passengers appreciated that they were sitting in something special.

But, tweaking the engine simply wasn’t going to produce enough power to justify the development of the Evolution Sport, so BMW decided to bore it out to produce a new, 2.5-litre engine. This capacity increase, along with bigger valves and a sportier camshaft saw power rise to 238bhp, a sufficient bump in power to warrant oil being sprayed on the underside of the pistons to help keep them cool. The production run ended up at 600 units, all of which had the Evolution 2’s full suite of weight saving features fitted. No matter that a decent dose of food poisoning would do more to improve the M3 Evolution Sport’s power-to-weight ratio that option deleting, owning a car with a smaller fuel tank and not having any interior grab handles, map lights, electric windows, or a sunroof, on-board computer, and air conditioning is way, way cooler than having them.

Only available in Jet Black or Brilliant Red with contrasting bumper stripes, BMW did give a little back to the customer in the form of black Recaro sports seats plus adjustable front and rear spoilers.

Further special editions included the (mainly cosmetic) Tour de Corse, Europa Meister 88, Johnny Cecotto and Roberto Ravaglia plus the rather odd M3 convertible.

DRIVING ONE

All BMW E30 M3s are left-hand-drive, which tends to be more of a theoretical problem than a practical one once you’ve got used to changing gear with the wrong hand. And changing is gear is something you’ll be doing a lot of because performance is strong rather than startling, with a sub-seven 0-60mph time and a top speed of around 150mph. But the M3 was never about outright performance, so if that’s your criteria for buying one you might be better off with something else. Like a Cobra kit car.

No, the M3 is all about the handling, and the handling is every bit as good as you’ve been led to believe. It’s an ultra-balanced, ultra-telepathic MX-5, or a slightly soft Caterham Seven with four seats and enough civility that you could cross a continent in complete comfort. It’s also very, very forgiving, but don’t think that means it’s an understeery dullard because it’s not. It just enables you to nibble away at the ragged edge until you are skipping over it at will in the sure and certain knowledge that you have to be a monumental bellend to get it to bite back.

The reason it is so nimble and forgiving is part perfect weight distribution, part diligent engineering, and part wieldiness, an important element of the equation that comes courtesy of the E30’s diminutive size and an all-up kerb weight of just 1,200kg.

Plus, of course, a lot of awesome, all topped off with a dash of legend. The E30 M3 is one of very few cars in which you can meet your hero and walk away awed by the reality.

copyright - Classic Car Auctions

BUYING ONE

Buying a car like the E30 M3 takes a lot of effort and if you ever feel like skimping the steps and rushing in where angels fear to tread, read this story. But, looking on the bright side, BMW did build more than 15,000 of them, so there are more than a few of them out there – and some of them are very nice indeed.

The first step is the obvious one; to check that what you’re looking at is actually a genuine M3, and this is the sort of question that should keep you awake at night, so join a club and do your research.

Once you’re convinced that what you’re looking at is The Real Thing, rust is going to be your biggest concern, so check everywhere: lift carpets, unclip covers, and peer and prod until you are happy that you understand the extent of the rust, because there will almost certainly be some.

It might be hard to believe now but prices of E30 M3s used to be on the floor, so you can expect that multi-owner cars will have been neglected at some point in their life, so a partial service history isn’t exactly unheard of at the bottom end of the market. If you’re floating around the top though, you’ve got every right to expect it to be flawless but remember that cars that don’t get used very often generally make a terrible buy if you’re looking for something to use properly. The main problem with not using a car on a regular basis is that things like rubber seals tend to harden and shrink, which leads to oil and fluid leaks galore. Mechanical components rust and seize too, which triggers a lot of faffery whenever you want to use the damn thing. Which means you won’t bother, which is where these sort of vicious circles start…

Accident damage is another worry as most, if not all, M3s will have been driven hard, sometimes on a track by people with more confidence than talent. The panel shutlines should be immaculate, so listen to the warning bells in your head if they’re not and a cracked fuse box lid is another (well hidden) giveaway that the car might have taken some hard knocks, so its worth checking that it’s in one piece and looks like it’s thirty years’ old rather than a new-old stock replacement that’s been fitted to hide a problem.

All the mechanical parts can be rebuilt, at a cost. Having said that, if it has been well serviced then M3 is a tough old bird, and it’s not unusual to see engines with 150-200,000-mile under their belt still running well providing they’ve been treated to fresh filters and oil on a regular basis and a new cam chain at 100k. A compression test will give you a good idea of what’s lurking within and an examination of the oil via a full analysis (something that is standard procedure in the heavy plant industry as part of the routine servicing of vehicles that are too valuable to have unnecessary downtime squandered on them) will tell you even more. It can be ordered online and sounds like £50 well spent to me, as long as the owner agrees to let you take a sample of engine oil and is happy to hold the car pending the results.

Not that it is necessarily prohibitively expensive to overhaul some of the M3-specific stuff when it does wear out; a noisy rear LSD might just need bearings and oil seals for example, and the suspension responds very well to nothing more than a full set of new rubber bushes.

Other than that, you need to look for all the little bits and bobs that make the M3 an M3; wheels are often the first casualty when owners try to ‘improve’ the car and so the more original it is, the more it’s worth. A copy of BMW E30 3 series – The Essential Buyers Guide by Ralph Hosier is probably worth the £20 it’ll cost you, too.

WHAT TO PAY

Firstly, don’t get suckered into buying a second-rate car because you think you can’t find a decent one because all the money is in the good cars, and it would be financial suicide to try and save a few quid by buying anything else.

Now that we’ve got that out of the way, it’s time to take a look at how much cold, hard cash it’s going to take – and you’ll need a lot of it because the very best cars are hitting six figures right now. However, cars that are merely very good can still be found for £50-60,000, while £30,000 seems to be the cost of entry for even the roughest examples. Which you shouldn’t buy.

Still, with prices rising by 40 percent a year your money is probably safe, so if you’ve got it just sitting in the bank doing nothing, you might as well indulge yourself.

copyright - Veloce Publishing

LOOKING AFTER ONE

A good rule of thumb, is that everything on an M3 costs three times as much to fix as it does on any other BMW 3-series, so looking after one is not going to be something you can get your local garage to do.

Or is it? The E30 M3 is, at heart, a relatively simple car from the eighties, so as long as they know what they’re doing any decent garage – and employ mechanics rather than fitters – should be able to look after it for you. If I were you, I’d get it serviced at a specialist initially as that will give you instant piece of mind alongside a wish list of stuff that needs fixing over the next couple of years. I’d then scour the Internet for genuine stuff to refurbish it, getting your garage to do the stuff you don’t feel comfortable doing yourself.

And I’d use the very best synthetic oil I could find.

MODIFICATIONS

You know what I’m going to say, don’t you? Well, you’re right. If you want to protect your investment then you’ll keep it stock and if it’s not stock, you’ll want to make it so.

However, if you had an uncontrollable urge to liberate another 50bhp by way of a chip tune then I’d have no objection, but anything more is tinkering for tinkering’s sake. After all, you don’t really think you know better than BMW’s M Division, do you?