If ever a car’s name unfairly lent it a gravitas that it would never be able to live up to, it was the Spitfire.

I grant you there are some similarities with its airborne namesake: the chassis is as crude as anything that originated in the WWII era, and yes, its cockpit is as cramped as that of a Lancaster’s rear gunner’s, but other than that the Spitfire was hopelessly ill-named; nominative determinism might be a thing for humans, but it clearly doesn’t work for cars.

By jimmyroq (http://flickr.com/photos/jimmyroq/230056905/) via Wikimedia Commons

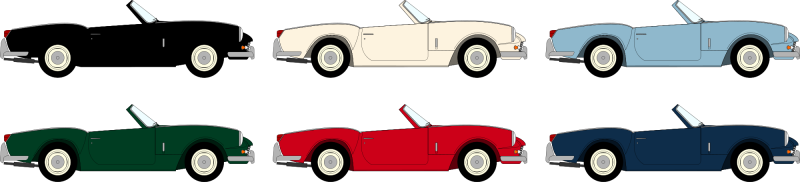

Spitfire MK1 (1962-64) and MK2 (1965-67)

Yet it started so well. Early sixties’ London was searching for a miracle; the Second World War might have ended nearly twenty years earlier but rationing was only an eight-year memory and free love and recreational drugs were still on the (very distant) horizon.

A good night out meant four pints of mild, half a packet of Capstan and a bag of scraps from the fish ‘n’ chip shop on the way home. If you were lucky you might have a quick knee trembler in the ginnel but luck was in short supply then, so you probably fell asleep in a half-drunken fug dreaming of the barmaid in the Dog and Duck, even if she did remind you uncomfortably of your mum.

So a two-seat sports car aimed at the working man was a revelation. Millions dreamed of being able to throw their car keys casually on the bar top, smile ruefully at the barmaid, and confirm that yes, that was their new Spitfire parked outside.

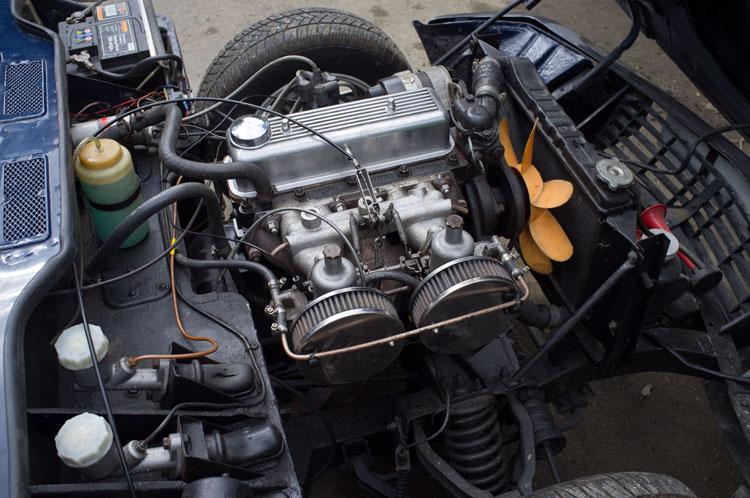

As a rakish convertible, it was easy to forgive the Spitfire’s lowly 1147cc engine. After all, 63bhp and 67lb/ft of torque was enough when your whole car weighed less than three-quarters of one of those new-fangled tonnes, especially given the lovely induction rasp of the twin SU carburettors.

Less easy to forgive was the violent lift-off oversteer caused by the almost criminally incompetent swing axle rear suspension that had a tendency to encourage the rear wheels to ‘tuck-in’, thus adopting crazy angles of positive camber. Many a half-drunk lothario quickly learned that the fear induced by doubting your car’s ability to successfully describe an arc around a bend pales into insignificance when compared to the fear that results when you try and do something about it by lifting off…

Triumph updated the MK1 Spitfire after just two years, replacing it a car that was substantially similar but featured a slightly more powerful engine and a slightly better interior.

By Akela NDE via Wikimedia Commons

Spitfire MK3 (1967-70)

The third generation Spitfire, introduced in 1967, added a bigger engine – a throbbing four-cylinder powerplant displacing a whopping 1296cc and 75bhp. It also gained a new front end, mainly to help crash resistance (Triumph had had a lot of experience by then in assessing accident-damaged Spitfires…) and the option of a hardtop and wire wheels.

The rear suspension remained unaltered, which meant that all that extra performance – a Spitfire could now reach 95mph after passing 60mph in just 13.4 – translated into an even bigger impact when your rear suspension tuck-in and spat you off the road.

Something needed to be done, and that something was the Spitfire MK4.

Spitfire MK4 (1970-74)

By this time the rear end was in danger of being almost tamed, thanks to the so-called ‘swing spring’ (cue much sniggering in the engineering department as they managed to sneak that past the gullible management). The new car looked more modern too, thanks to a face-lifted front end and a fully redesigned rear.

The interior was much better too, and now featured such luxuries as a full-width dashboard and even a smattering of wood from 1973.

However, true to form, the powers-that-be at Triumph managed to cock things up royally by detuning the engine from 75bhp to just 67bhp while simultaneously charging the punter even more to buy one.

Hardly living the dream, was it?

copyright - Historics at Brooklands

Spitfire 1500 (1974-80)

Almost unbelievably, the Spitfire managed to cling on to life until 1980. By then the management viewed it in the same way Prince Charles views his mum.

Yes, the engine was now an almost adequate 1500cc and yes, the rear suspension continued to be tuned and honed and could no longer be relied upon to kill the unwary. But it was a dog in need of a bullet, something it received in 1980. The last of the line was an Inca Yellow with a hardtop and overdrive. Triumph didn’t have the gall to sell it, and relegated it to a museum, where it languishes today.

Driving a Spitfire

Driving a Spitfire is a nicer experience that I might have led you to believe. That vintage-era engineering might not deliver Elise-like handling but there is a huge amount of pleasure to be had in pedalling one along at a steady 40mph-or-so with the roof down and the soft summer wind ruffling your hair. Pedants, or realists, as they’re more accurately described, might find that the gear change is as agricultural as the suspension, and the brakes are a bit wooden and barely adequate, even for such a light and slow car.

Oh, and the cabin is a tight fit, even for those slim of stature and short on height; anyone over about 5’ 10” is going to struggle, especially in the early cars.

By Stahlkocher via Wikimedia Commons

My Spitfire experiences

By now you might be thinking that I’m a typical Google journo, out to ridicule your pride and joy for cheap laughs.

Of course, you’re right but at least I’m speaking as an ex-owner of not one, but two Spitfires.

You see, my first real car was a Spitfire. It succeeded a succession of Citroen 2CVs and GSs, all bought for peanuts and MOT’d by a half-blind alcoholic; £15 bought you a three-year-old MOT failure (yep, you read that right. The Citroen GS/GSA was failing its first MOT in droves back in the eighties…) and another few quid on a tub of P38 and some underseal meant an assured pass, as long as you took it for testing on a Friday afternoon.

So a £500 Spitfire, even if it was yellow, was a real step up for this eighteen-year-old. Forget the rampant rust, ill-fitting hood, and wheezy performance, I thought I was King of the Hill in that car.

Well, I did when it was running. While my GSs, long renowned as almost unfathomably complex, ticked along quite nicely (and tick is exactly what they did. For some reason every single one I ever had suffered from worn camshafts and followers, and at £15 a pop there was simply no point in doing anything about it other than popping in the odd can of STP oil treatment every now and then), the Spitfire was easily the most unreliable car I ever owned – until I traded in a Spartan kit car on a Talbot Horizon, that is.

I eventually sold it to the lady at the Derby Evening Telegraph that took the small ads over the phone. She was worried about a conflict of interest, so paid the full price sight unseen as long as I didn’t mind not placing the ad; she was worried she’d miss out, whereas I was worried that she’d come to her senses and back out, so agreed not to place the ad and saved a tenner there, handed the car over to her boyfriend and refused to answer the house phone for weeks afterwards. I’d like to say that her professional guilt helped assuage mine, but I was just glad to have shifted it.

Thirty years later I found myself driving a newly purchased MK4 Spitfire home from an auction in Harrogate. I dodged motorways as the 1296cc engine (recently detuned, you will remember…) wouldn’t hit 50mph, much less 70, and the lights were dim, the wipers didn’t work, and it was dark and lashing down with rain. It stands out as one of the most terrifying drives of my life and I didn’t drive it for three months. When I summoned up the courage to back it out of the garage it threw a valve pushrod. I repaired it, sold the car on, and keep the bent pushrod as a warning never to consider buying one of the bloody things ever again.

Buying one

If, despite my well-intentioned advice, you insist on buying a Spitfire, the good news is that your pre-purchase inspection will be almost completely limited to searching for rust. The trouble is, there are a lot of places where it can lurk – and, despite having a separate chassis, the Spitfire also relies on the integrity of its outer sills to lend the bodyshell some rigidity; if they’re rotten, your car will be flopping around like a New Romantic’s hair and will handle even more badly than usual, which is quite some feat.

Nor should you ignore a rotten front clamshell. It isn’t structural but it is expensive and hard to fit, so a good one adds a considerable sum to the car’s value.

The oily bits are cheap and easy to replace, so I wouldn’t be put off a car that was structurally sound but poorly maintained. The reality is that you are going to be spending more time repairing it than driving it anyway and most of us find that mechanical work is much, much easier than bodywork…

What to pay

Prices start at a few hundred pounds for a basket case and rise to an almost unfathomable £20,000. Not that you need to pay anything like that because £5,000 will get you a very nice, usable MK4 or 5, which are the ones you want if you’re going to actually use the bloody thing.

By Avaldia via Wikimedia Commons

Restoring a Spitfire

The question isn’t whether your shiny new Spitfire will need restoration; the question is whether you’ve been astute enough in your pre-sale inspection to spot everything that needs doing and budget accordingly. (If you do manage it, please drop us a line and tell us your secret; we’re far more used to getting sucked into buying a dog on the premise that things can’t be as bad as they look, when, as we know, where old cars are concerned things are always worse than they look.)

The upside of owning what is a relatively crudely engineered car is that a chimpanzee with an adjustable spanner and a hammer could restore one, a situation that is helped by the spares situation, which is unrivalled by anything this side of an MGB.

Rimmer Bros and Moss Europe are the established go-to guys for all your Triumph Spitfire needs, offering a wide range of parts, accessories and upgrades, including the sort of hard-to-find trim that can stymy even the most carefully planned restoration. (If you own a MK3,4 and 5 Spitfire then you could also try SC Parts Ltd who should be able to help too.)

Upgrading a Spitfire

A Spitfire isn’t subject to the usual classic car vagaries and, bar the very top end which consists almost completely of trailer queens whose tyres will never again meet tarmac, you should feel free to upgrade and modify to your hearts’ content.

For most people this means getting the cooling system working properly and controlled by an electric fan, adding a modicum of extra power via a better exhaust manifold, upgrading the lights so you can see where you’re going, and adding an electronic ignition system conversion that gets rid of those pesky points (although it’s nearly always the condenser, rather than the points, that fails, which is something worth trying next time you’re stranded on the hard shoulder…).

The next stage might be replacing the steering rack mounts with billet aluminium versions to sharpen up the steering response, fitting an electric fuel pump, and upgrading the brakes so it will actually stop when you press the middle pedal. Finally, you can tweak the suspension geometry to tune the handling to your own taste but given that Spitfire handling is an inexact science at best, I wouldn’t lose too much sleep worrying about it initially.

Or you could save yourself a whole world of pain and expense by buying an MX-5.

Carlton Boyce