The Alfa Romeo Spider was never a quick car, not even when viewed through The Summer of Love 1960’s rose-tinted glasses. Nor was it, to my eyes at least, especially pretty after it has metamorphosed into the series 2 (and later) cars. The interior is also quirky to the point of being downright uncomfortable, it rusts like there is no tomorrow, and the electricals are as reliable as you might expect of an Italian car built five decades ago.

And that’s without touching on the sometimes iffy handling, somewhat less than oil-tight engines, or the leaky roof: an MX-5 is so much better than the Alfa is every single area that the two cars might as well be from different worlds – and before you complain that they were designed half-a-century apart, may I remind you that in the nineties they fought head-to-head for the same customers?

That its appeal endures proves two things: that the lure of the Alfa Romeo badge is as strong now as it’s ever been; and that charisma is a funny old thing, because, no matter what its faults, the Alfa Romeo Spider has it by the bucketful.

History

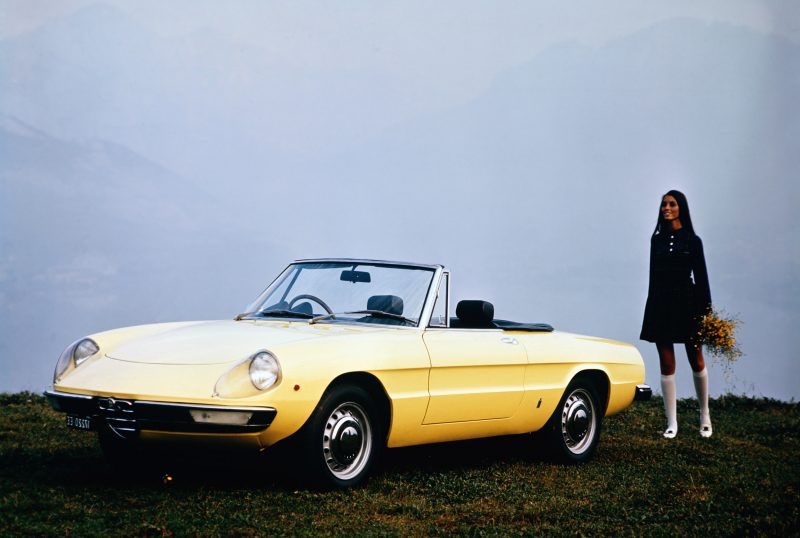

The Alfa Spider splits is essentially a game of two halves: the early ‘boat-tailed’ cars, which were built between 1966 and 1970; and the later cars with a squared-off, Kamm-style rear end.

Nineteen sixty-six not only saw England beat Germany 4-2 to win the FIFA World Cup, it was also the year in which the world witnessed the first non-manned moon landing, Simon and Garfunkel’s Sound of Silence reach the number one spot in the American Billboard charts, and Cassius Clay beat Henry Cooper in London to retain his title as heavyweight champion of the world. It also saw the unveiling of the Alfa Romeo Guilia Spider at that year’s Geneva Motor Show, which might be of more interest to our readers.

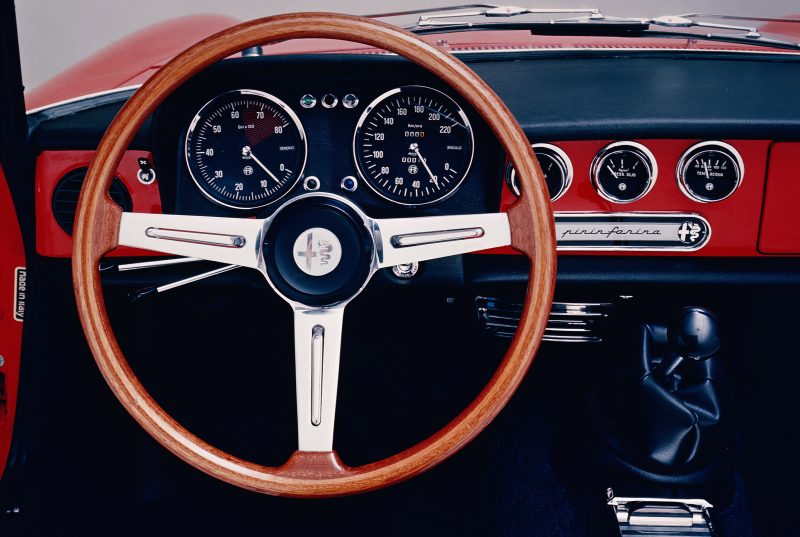

The Spider story started well. The body, designed by Pininfarina, sits atop the 105-series Giulia platform, which meant a lovely little twin-cam engine under the bonnet, twin carburettors to give it an addictive rasp under acceleration, a five-speed gearbox to send the power to the rear wheels and all-round disc brakes to bring it to a prompt halt. So, nothing to complain about there.

Nor is there anything to complain about the way it looked; the original cars are achingly, hauntingly beautiful, being delicate and perfectly proportioned; Kylie on four wheels, if you like.

Which makes them the ones everyone wants, lifting the price accordingly. Originally fitted with a sweet little 109bhp, 1570cc twin-cam engine (102mph and 13 seconds to 60mph), they were upgraded with a larger 1750cc lump with 118bhp after just eighteen months. The chaps at Alfa didn’t neglect the chassis either, fitting better brakes and sharper suspension to help the keen driver rein all those extra horses. The top speed rose to 115mph, while the 0-60mph dropped to nine seconds’ dead.

And it couldn’t stop fiddling, upgrading the Spider again just eighteen months later, this time with a 2000cc engine under the bonnet that developed 132bhp, a move that raised the top speed to 120mph and lowered the all-important bragging-rights acceleration time to 8.5 seconds.

These two-litre cars, built from 1970 onwards, might sound like a great idea (more power equals more better, right?) but it also royally screwed up the styling at the same time, replacing that elegant rear end with a squat, Kamm-style backside that looked like a duck’s arse in the midst of squeezing one out. The aim was to make it look a bit more modern, which I suppose it did, albeit in the same way as a German pillbox looks more modern than Westminster Abbey.

For a company that was so assiduous in developing the Spider in the sixties, Alfa then did nothing of any note to it until it gave the Spider new front and rear bumpers in 1983, thus creating the series three. The new bumpers – black rubber and there to meet increasingly stringent impact legislation – made it look even more awful, obviously.

The interior was heavily revised at the same time, losing its earlier period charm in the name of better accident safety and marginally improved ergonomics. The boot lid received an ungainly rear spoiler – and never was an appendage more aptly named because the extra drag it created and the additional weight of all that legislative equipment dropped the 0-60mph acceleration time by half-a-second, even if the top speed was still a decent two-miles-a-minute.

Nineteen-ninety introduced the world to the series four Spider. The main change was the deletion of the twin carbs in favour of Bosch fuel injection alongside body coloured plastic bumpers front and rear, which sharpened up the styling a lot. Power steering made an appearance and an automatic gearbox was now an option too. Alfa even manged to cobble together the wiring loom to make way for an on-board diagnostic system.

The Alfa Romeo Spider died in 1993, outclassed in every single area by its competitors. The lithe, utterly gorgeous 930kg early car had been transformed into something akin to a Vegas-era Elvis, eventually tipping the scales at more than 1100kg: still impressive compared to today’s bloated efforts, but a million-miles away from Pininfarina’s original design.

Driving one

A large part of the Alfa’s charm is its foibles, the most obvious of which is the interior: the gear-lever sticks out from the dashboard at a peculiar angle, meaning that the Spider’s gear changes move in what is almost a vertical, rather than a horizontal, plane. This is a wonderfully evocative touch that instantly lifts the Italian car above the coldly efficient Germans and Japanese.

But it’s not all good news. The Spider does feel a bit disconnected to drive; scuttle-shake is ever-present and the drivetrain feels a bit loose and almost wobbly at times. But the steering is sharp and the engine – no matter what era or capacity – is free-revving and a joy to stretch.

The twin Weber carbs make a lovely sucking, rasping noise; the later fuel injected cars might be easier to live with but I’d trade noise for practicality every time in a car like this unless you’re going to be using it every day.

Buying one

Rust, rust, and then rust are the three things that will come back to haunt you if you skimp on the pre-purchase checks. The wheelarches, sills and floorpan are the most vulnerable areas, with the driver’s side footwell generally being the first place to go. Repair panels are available but given that it’s always better to let someone else pay the big bills I’d rather pay a bit more for a good car in the first place than try and save a few pounds by buying a dog in the hope I could restore it myself.

Other than rust, it’s worth checking that the panel gaps are even as accident damage isn’t exactly unheard of, followed by a quick sweep of the bodywork to check for excessive quantities of filler.

The majority of the mechanical components are simple to access, reasonably easy to source and cheap to buy, so a tired engine or dodgy brakes shouldn’t necessarily stop you from buying an otherwise good example.

The aluminium engine is known to leak oil, so don’t worry about the odd drip and streak on the block and sump, and oil in the spark plug recesses is almost always a sign of a leaking oil filler cap seal rather than anything more serious.

On the other hand, the cooling and brake systems, rear axle, and gearbox shouldn’t leak at all, so stains and damp patches are probably going to need fixing sooner rather than later. This shouldn’t be seen as a deal-breaker, more something that can be used as leverage to drive down the asking price.

The steering rack shouldn’t have more than an inch or so of free play at the wheel, and the synchromesh on second gear is notoriously poor; most owners just put up with it and take their time when moving through it as it’ll never be a journey-stopper, no matter how bad it gets.

Of course, the Alfa Romeo Spider S3 and S4 were never offered as factory right-hand-drive cars, so if you find one then it’s going to be an aftermarket conversion, the quality of which is hugely variable. Anything done by companies like Bell and Colvill or Lombarda Carriage Company will be fine; check for a sticker on the door jamb, or even a plaque, to tell you who did it. If you can’t find anything then tread carefully; the quality of the brake servo relocation and sundry electrical work is said to be frighteningly bad on home home-brewed conversions…

What to pay

Despite costing roughly the same as a Jaguar E-Type or a Lotus Elan when it was new, the Alfa Romeo Spider still hasn’t joined the Brits’ rocketship appreciation curve, which makes it look under-valued to me. Prices have only risen very gently in the past decade or so and there are plenty of bargains to be had, even if some sellers are marketing their cars with more of an eye to what they wish was happening rather than what actually is.

Because the reality is that even the very best series one cars struggle to reach £30,000, while a very nice everyday driver from the eighties or nineties can be picked up for a four-figure sum. Show-quality cars fall somewhere in between the two but there is no need to pay more than £20,000 for anything other than a good S1.

Project cars – almost all of which will have been neglected for decades on account of having such a low value that they didn’t warrant their owners spending much on them to keep them on the road – can be picked up for under £2,000 but I wouldn’t recommend buying one. With good cars as cheap as they are, there really isn’t enough of a difference for you to swap a few grand for a couple of years of your life unless you really can’t afford anything better; you won’t save money doing it yourself but I suppose you will at least be able to spread the cost over a few years.

Running one

The reason the sills rust so badly is because the factory didn’t think to fit them with drain holes to let the water that collects inside them out again. Don’t be like Alfa; get a couple of holes drilled on each side and then flood the sills with a decent rust-proofing fluid.

You should budget to change the engine oil every 3,000 miles, which should still be cheap insurance even given the high quality of today’s synthetic oils.

The engine timing chain needs to have its tension checked and adjusted every 6,000 miles, and the valve clearances will need checking and shimming as necessary every 12,000 miles too, which is a bit of a faff but utterly essential.

Did you know?

The first Alfa Romeo Spider was perhaps the first example of crowd-sourced marketing, the name ‘Duetto’ having been the winning submission in a 100,000-entry competition the company ran to find a name for its new convertible sportscar. And if you ever need proof that the sixties were kinder, gentler, more mature times, no one to the best of my knowledge, submitted the name ‘Boaty McBoatbum’, despite the gorgeous new Alfa boasting an undeniably boat-influenced rear end…

Carlton Boyce