The current fad for presenting ‘barn-find’ cars as a blank canvas for potential bidders is worrying me. While the opportunity such a project offers for reincarnation in its new owner’s image is entirely understandable, we are standing at the same precipice as house buyers were in the twentieth century. That they spent the best part of five decades ripping out original, period features to clear the way for the installation of more modern ‘improvements’, leaves 21st century home owners tearing their hair out in frustration at what is now seen as having been an especially bleak period of cultural vandalism.

We are more enlightened when it comes to restoring old properties now, with architects and archaeologists now rightly placing the emphasis on preservation rather than restoration, a more sympathetic approach that simultaneously side-steps the perennial restorer’s dilemma of exactly which slice of its life the finished item should reflect…

So, we now find ancient stone walls reinforced and strengthened with a material chosen for its utility rather than ability to blend in with what is already there. There is no attempt to fool the viewer with a clumsy and heavy-handed attempt to seamlessly blend old and new; the new is clearly new and plays only a supporting role to that which has stood the test of time over centuries past.

If further reinforcement is needed then it might come via carbon-fibre rods inserted and glued into holes drilled to stabilize and support crumbling walls; in situations where too much stonework has fallen away to attempt a patch, internal reinforcement at least preserves the monument as it is now, freeze-framing it forever, albeit in a partially dilapidated state. It is an honest acknowledgement that nothing lasts forever.

But what, I hear you ask, does this have to do with cars? Simply that we are, in my opinion, ruining many important classic cars with ill-judged, age-inappropriate restoration that erases vast swathes of its history in the name of expediency. Too many owners lose sight of the heritage of the vehicle they’re seeking to preserve, shooting for the stars in a ground up, nuts ‘n’ bolts restoration, ending up with something that is as shiny as they can possibly make it and often far better than anything the factory could have produced using the materials and tools available to them at the time.

Blame concours competitions if you must, but which of us hasn’t admired a better-than-new classic, twinkling in the sun at our local car show? (Of course, the fact that 100-point concours cars are pretty much undrivable, is one of the classic car scene’s dirty little secrets.)

Kevin McCloud, presenter of Channel 4’s Grand Designs, writer and designer, argues for what he calls ‘Conservative Repair’ (what we probably used to call refurbishment) instead, reasoning that once you’ve addressed the structural integrity of a project, staving off further decay is cheaper and easier than effecting repairs later in the life cycle, as well as being more honest and preserving more of the item’s integrity.

So, while replacing your Land Rover’s chassis with a modern replacement might be acceptable – although piecemeal repairs would be a more honest, if less attractive, more costly, and ultimately a less satisfying way of going about doing things – buying new panels wholesale probably isn’t. As Kevin succinctly puts it, bodywork should be:

“resprayed here and there where necessary to look beautiful from six feet away, cherished from three and authentic from six inches.”

How many of us would have the confidence to wheel out a classic with paintwork like that? Not many, I’ll wager, and I used to include myself in that. My (recent, and not entirely complete) conversion came via my new Arctic Trucks D-Max, an indulgence I could barely afford and one that weighed heavily on my conscience as a result. That it suffered a rash of scratches and scuffs following some heavy duty off-road sessions was the cause of further concern; how could I square squandering so much on a new car that now looks distinctly secondhand after just three months in my hands?

The pain started with the first scuffed alloy wheel, damage caused by my inattention when passing an errant rock on a Welsh mountainside rather than a shameful lapse of judgement involving a kerb in a Tesco car-park, I hasten to add. Close inspection will also reveal scratches along the flared wheelarches, all inflicted when squeezing through an overgrown section of green lane. (Gorse might be pretty, but it isn’t half scratchy.)

This damage generated an internal argument as to how and when I would manage this and any subsequent damage: constant restoration of wheels and coachwork would be time consuming and prohibitively expensive, while leaving it raw and unaddressed would be unthinkable.

My pragmatic solution is to refurbish it in sections as and when required, to polish out what I can and then to not lose any sleep over any minor scuffs and scrapes that remain; it’s a working vehicle after all, bringing with it a long and proud heritage via Arctic Trucks, and I have faith that Kevin would approve of my decision. In twenty years’ time, I’m sure the D-Max’s paint will have rubbed through in places, and be a little rough around the edges in others. But – and this is an important part of my reasoning – it will be authentic and honest and beautifully patinated. It will tell a story and remind me of the adventures that I’ve had in it. It’ll be something to pass on to my children in the hope that they’ll continue to use it for the sort of driving it was built for rather than turning it into a static display that serves only to remind them of what was, rather than what might still be.

Which is where I have such a problem with modern replicas like the Jaguar E-Type Lightweight and XKSS or the Range Rover Classic and Land Rover Series 1, all of which come courtesy of their original manufacturer, presumably in the hope that they’ll come with an authenticity and a provenance that would otherwise be absent given the obliteration, or, in the case of the replicas a complete absence, of any evidence that they are actually old cars.

Which is a fool’s errand, obviously because they’re nothing but fakes, albeit beautifully constructed ones, built solely to make a few quid for JLR and to revive a heritage that should be a living embodiment of the company’s values rather than a backwards-looking mock-Tudor mansion.

These are cars that will be bought by collectors, who will do nothing with them other than use them to show off with; automotive masturbation in its most vulgar form. If any of them are bought to be used, to be driven down into a condition where they need further restoration to remain roadworthy, I’ll eat my metaphorical hat: Love him or loathe him, there just aren’t enough car guys like Jay Leno: ”I like to restore a car to 98 or 100 points, then drive it down to 10 or 20 points.” Hallelujah, say I, and pass me the car keys.

And please don’t think that I’m decrying JLR on the basis of the quality of the work it undertakes, or the value the finished cars provide. My argument is simply that when it restores a series Land Rover or a Range Rover Classic, it picks the bones clean, leaving absolutely nothing of the original vehicle. It trumpets the fact that every single item is disassembled, restored, polished, and buffed, when all I see is vandalism.

The interior of the Land Rover Series 1 it creates is simply beyond reproach. It’s beautiful, utterly wonderful and easily the equal of anything you might see at Pebble Beach or any of the other top-flight concours d’elegance events. Which is ironic, because the original vehicles were, by very definition, a triumph of function over form. The new model is an insult to the honesty and the veracity of the original, and while I can understand JLR’s desire to get a slice of this highly profitable pie, I can’t help but think its attentions would be better invested elsewhere. Like preserving the wrinkles and the creases and the scratches that were wrought over the years by people that loved the car. People who cried in it, and laughed in it, and kissed in it.

Because, surely, part of what we buy when we buy an old car is its heritage, its history. We never buy just a car, we are always buying its cultural legacy and seeking, consciously or unconsciously, to inherit all the associations that come with it. And some of those associations come via its imperfections.

Let me put it another way: value aside, would you rather drive a genuine ex-Trans Americas Range Rover Classic, or a re-manufactured Range Rover Reborn? Or a genuine E-Type Lightweight with period racing provenance and a few battle scars to prove it or an Eliza Doolittle pastiche that only exists because an eagle-eyed accountant discovered half-a-dozen ‘missing’ chassis numbers? (And, lest you think I’m being unnecessarily snarky, the apostrophes are Jaguar’s, not mine.)

Yet even this is a slippery slope into potential parody. It is alleged that one manufacturer (not Lola, despite the photograph) now wheels its racing cars away with an eye to future display – and the purity of that image is at risk if the mechanics are careless enough to remove any of that hard-earned road film as they push it around the pits. Is that any better, any more honest, any more genuine than a car maker exploiting a numbering anomaly in a decades-old ledger to re-manufacture a limited run of vehicles?

There are lessons to be learned for mere mortals even in this rarefied world, the chief of which is that we should try to be honest in all we do when it comes to looking after our old cars. This might mean not rushing in to replace a component just because it’s a bit crusty when a few minutes with a bit of wet-and-dry and a rattle can of paint might see it back in serviceable condition. Or it might mean accepting stone chips on the bonnet, faded badges, or a shiny steering wheel.

And those cracked, dry, dirty leather seats? Why not unbolt ‘em from the car and spend a few hours cleaning and feeding them? Have the horse hair stuffing replaced if you must, and by all means paint the frame if its rusty, but the patina they wear has been hard-worn and must be preserved if for no other reason than you are only a temporary custodian of it; at some point it’ll belong to someone else, and you owe it to future generations to preserve it as best you can.

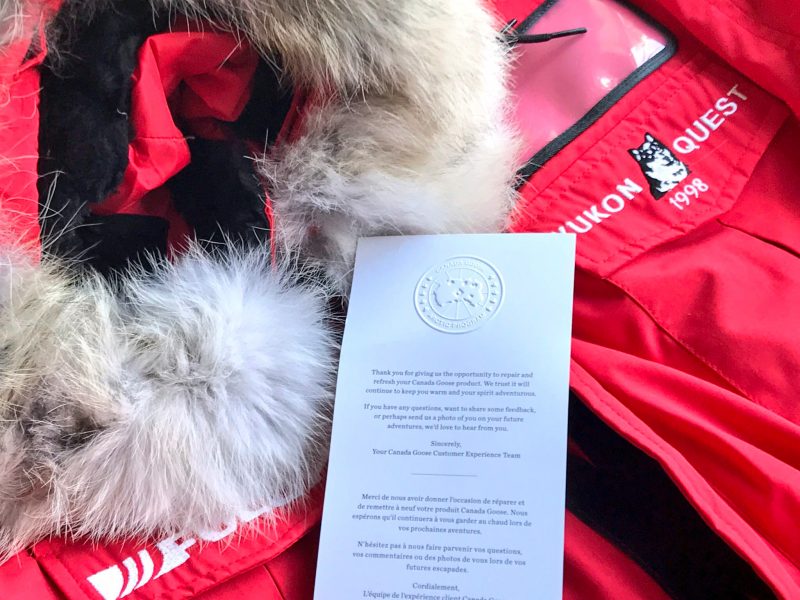

This is an ethos that extends to other sphere of activity, too. My old Canada Goose parka, nineteen years old and counting, wasn’t warding off the cold as well as it used to and I’d lost the fur ruff at some point in the past, too. The solution was refurbishment back in the Canadian factory that made it in 1998; the down filling was topped up free of charge under the provisions of Canada Goose’s comprehensive lifetime warranty, while a brand-new coyote fur ruff cost just £40. Now, not only is that great customer service, but it has revived an old friend for a fraction of the cost of a new one. That’s an aesthetic win, as well as a monetary one.

Old watches are another niche interest in which thoughtful refurbishment is prized over inappropriate restoration, and while I do take issue with the over glossy paintwork of some of his work, that Rick Dale of American Restoration is as punctilious as he is in his determination to reuse every last screw and nut to try and preserve the integrity of the item he’s working on goes a long way to redeeming him in my eyes.

‘Built, not bought’ is the motto of our friends in the arcane world of the car customiser. Perhaps ‘refurbish, don’t restore’ could be ours.

Carlton Boyce