The Datsun 240Z is an anachronism in more than just name; it’s a hairy-chested, tail-happy, uncivilized seventies sports car with more Gene Hunt in its DNA than is healthy.

And yet, it was a huge success with well over half-a-million eventually finding homes worldwide in the hands of enthusiasts that prized its reliability as much as its looks and performance. But, as with so many Japanese cars from that decade, the 240Z has a well-deserved reputation for returning to its elemental state with alacrity, so few remain in anything like original condition.

But, if you can find one, they’re a helluva thing…

History

Datsun’s goals with the 240Z were lofty: to ape cars like the Jaguar E-Type, MGC, and Triumph GT6 in style and dynamic ability but with an added layer of reliability that would surprise and delight a world of drivers used to waiting for the AA to arrive in a layby somewhere outside Corby. In the rain. In a leaky British sports car .

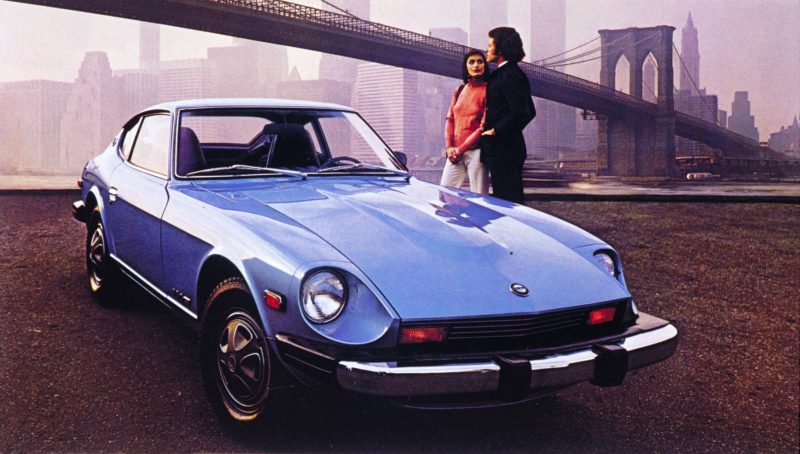

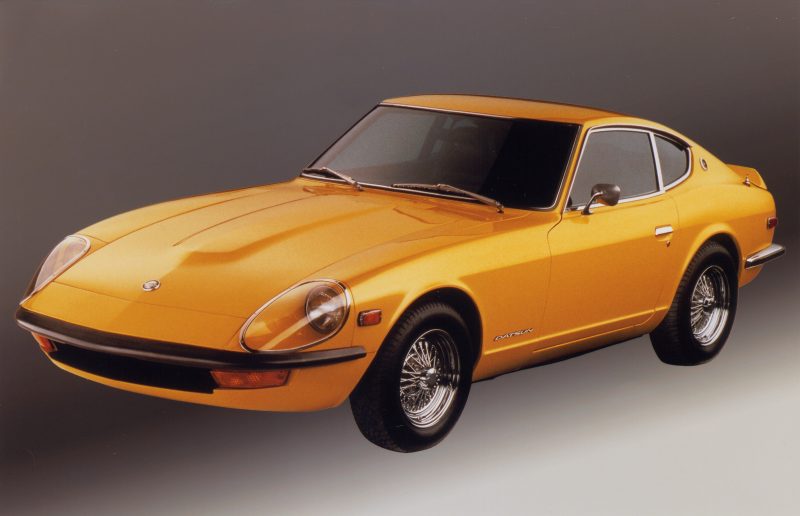

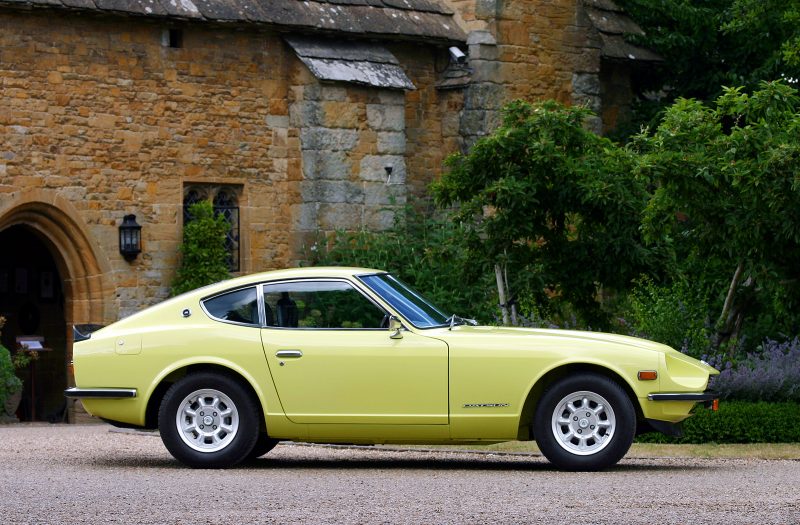

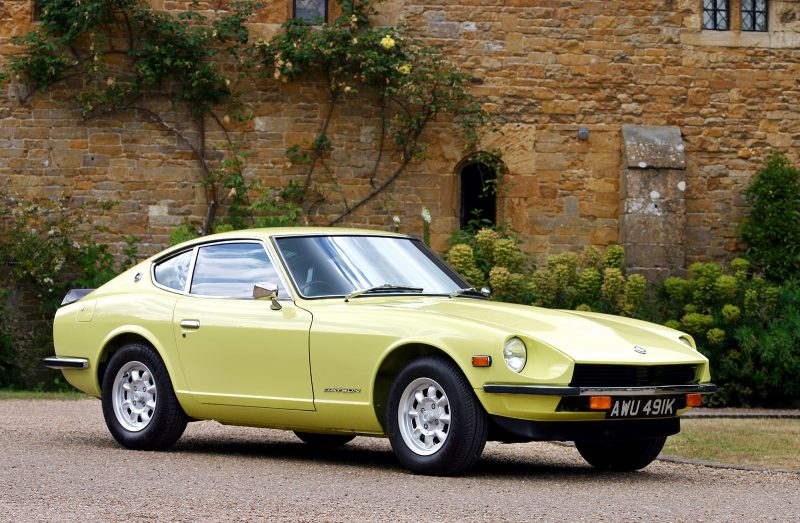

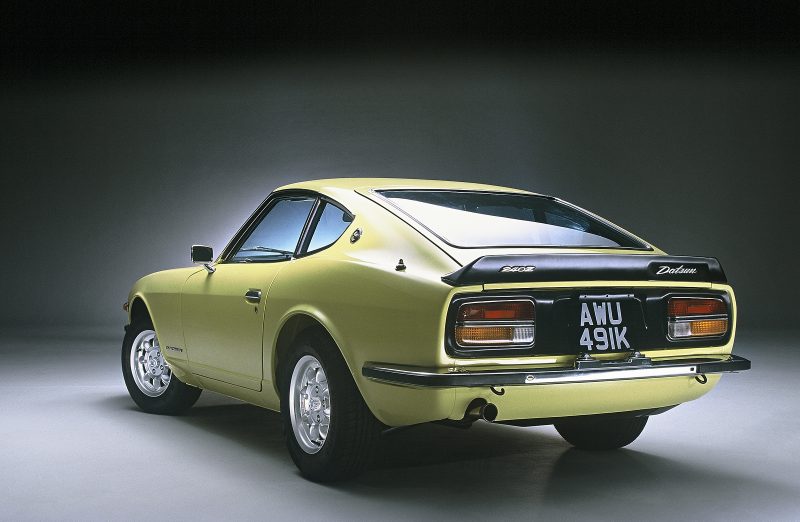

Given this, it should come as no surprise that the 240Z’s styling was derivative rather than ground-breaking but that’s alright because it is a very, very good looking car. As well it might be: a long bonnet, steeply raked windscreen, and a Kamm-style tail are all tried-and-trusted ingredients when you are building a traditional sports car.

As is a dark, predominately vinyl interior with two front bucket seats and a deep-dish steering wheel that takes its inspiration from the Italians rather than the British. Which means the instruments are set deep inside Alfa-esque cowls and the driver is forced to adopt the sort of laid-back driving position that will be familiar to anyone who has ever watched just about any car chase scene set in the seventies.

While the general formula might be a familiar one, the Japanese went on to do what the Japanese excel at, populating the 240Z’s steel monocoque with all the good stuff: a 2.4-litre straight-six engine that developed 151bhp and 146lb/ft. of torque; feeding that power through a five-speed manual gearbox; bolting on front disc brakes; and hanging the wheels off an independent rear suspension set-up. Admittedly, none of this was ground-breaking in and of itself but the combination was way more than the sum of its parts.

October 1969 saw the release of the ‘series one’, which can be identified by a rather nice chrome 240Z badge on the pillar and two horizontal vents on the rear hatch just below the glass. The series two cars arrived in mid-1971, and can be identified by the deletion of the chrome 240Z badge in favour of the letter ‘Z’ inside a circular emblem. The rear vents also went AWOL, reappearing in the C-pillar instead. Engine refinement was said to have been improved too, although no-one seems to have noticed much of a difference in reality.

The 240Z died in 1973 and was replaced by the 2.6-litre 260Z, which came out in 1974 and was available in the UK until 1978. A 2+2 version of the 260Z was also built on a 12-inch longer chassis; neither are as popular or collectable as the original 240Z.

Driving one

It’s easy to forget that cars of this period are seriously light, so while that 2.4-litre engine isn’t over-burdened with power it only has to haul just over a tonne in weight, which helps performance, handling, and efficiency. The 240Z won’t set your pants on fire in the same way as something similar from the nineties might but there is a charm to its throaty engine, ever-so-slightly wayward handling, and puppy-like eagerness.

What power there is – and 151bhp is more than enough for most people, given how light it is – is easily accessible thanks to a decent throttle response and a set of well-spaced gears that help you keep the straight-six on song. Driven hard you’ll hit 60mph in around eight seconds and if you keep the throttle pinned to the floor for long enough you might eventually see 125mph.

The absence of weight helps the ride too, which is more pliant and forgiving than you might imagine, making the 240Z less of a bone-jolter than most of its rivals although the suspension can bottom out on fast, bumpy B-roads. However, all is not lost because that slightly soft suspension gives you a lovely bonus in that it helps with weight transfer, letting you throw the car about in the sure and certain knowledge that you know exactly what is happening beneath you: simply brake and turn in, loading up the front outside wheel. Then pause for just a beat to let the whole thing settle before nailing it in the latter third of the corner, at which point you’ll discover that the Datsun squats very satisfactorily as it hurls itself towards the next bend .

When you don’t want to play the 240Z is happy to amble along, returning 30mpg with ease. The gearbox might be a little heavy in operation but it is still a joy to use, and while the brakes aren’t up to modern ABS-aided standards they don’t have too much weight to haul up either, so you’ll find little to complain about as long as you’re sensible.

Contemporary road tests commented on the car’s sometimes wayward steering, saying it was overly sensitive to cross winds and devoid of feel. Modern tyres appear to have helped a lot, as does fitting a complete set of uprated suspension bushes; thus equipped, most owners find little to complain about.

Could you use one as an everyday car? Hell yes, especially if you retro-fit it with a few carefully chosen modern components to further aid its already very good reliability…

Modifications

Owners who choose to modify their 240Zs tend to fall into one of two camps: either tuning for outright power, often in order to compete in historic rallying or racing; or modifying to improve the 240Z’s already very good reliability in order to use one as an everyday driver.

For the former, stroked engines are common, with capacities between 2.8 and 3.2-litres being the most common if fitting a hotter camshaft and free-flowing exhaust followed by some careful tuning of the fuel and ignition systems doesn’t liberate enough extra power for you. How powerful your engine can be is a direct correlation with your willingness to spend money but 200bhp is available via conventional tuning methods, and even the 300bhp that a bigger engine should deliver shouldn’t break the bank or destroy its usability.

Various states of tune are available for the suspension system off-the-shelf, and you’ll be able to spend a glorious few evenings deciding exactly how you want to balance comfort and performance – and if you’re still undecided, why not go for a set of adjustable dampers that can be varied depending on what you’re going to be using it for?

Finally, the upswept twin exhaust pipes look terrific in stainless steel and even better with a ceramic coating.

If you’re curious about what a road-going racer can look and sound like, here’s some inspiration:

If you fancy using a 240Z as your everyday hack (and why wouldn’t you?) there are plenty of folk that will upgrade your brakes, gearbox, engine, suspension, and even the wiper motor and linkage to turn your classic Datsun into something better suited for 21st century roads and traffic.

This sort of retro-dating suits the car very well indeed and shouldn’t have a detrimental effect on the value, especially if you keep all the old bits in case a future owner wants to trade usability for originality.

The modern Datsun 240Z

American interest in the Datsun 240Z was so great that Nissan even offered fully rebuilt examples in the late nineties, complete with a 12-month, 12,000-mile warranty. The ‘Vintage Z’ programme, administered by ten specially designated ‘Z Stores’ dotted across the ‘States, filled a gaping chasm between the outgoing Nissan 300ZX and the yet-to-be-released 350Z.

Nissan initially thought it might sell around 200 cars, a figure that was soon found to be woefully optimistic because despite replacing more than 800 components and completely disassembling and restoring everything else, enthusiasts baulked at paying $27,500 for a car they thought would end up being worth less than an original example.

Yes, the market had decided that a fully rebuilt, good-as-new Datsun 240Z was less desirable than one that hadn’t benefited from the tender ministrations of the very company that had designed and built it.

Funny old world, isn’t it?

Buying one

Rust on the sills and rear wheelarch is common, with the latter being notoriously hard to repair properly. To make things worse, the likelihood is that previous owners have just bodged a patch repair rather than doing it properly because it probably rusted through when the cars were still as cheap as chips and thus not worth spending a fortune on.

You should lift the carpets too as the floorpan is another place where rust tends to take hold if water has ever got in there. Which it probably will have. The other key area to examine is where the front chassis rails meet the bulkhead; if you find serious rust here – and if there is any then it may well be hidden beneath a thick crust of strategically placed underseal – then the car is probably too far gone to be saved.

The interior is fragile and prone to showing lots of wear, so don’t be surprised if the inside of the car you are inspecting is considerably worse than the exterior. Dashtops tend to crack if they’ve been exposed to the sun for lengthy periods and replacements are rare, although you can buy covers to at least try and disguise the damage.

Other than that, any half-decent car trimmer should be able to sort seats and door panels out for you, even remaking some hard-to-find items if necessary.

Body panels are readily available as are all the mechanical bits, so the odd rusty panel or worn-out component shouldn’t necessarily be a deal-breaker and might, if the price is right, even serve as an excuse to start modifying your new toy…

One interesting shortcut as to whether you are looking at a good ‘un is the under-bonnet torch; if it’s there and working the chances are that at least one of the previous owners was a bit of an obsessive, which can only be a good thing. Similarly, the two rear cubbyholes located behind the front seats should house a jack on one side and the original toolkit on the other. If they’re there, that only says good things about the care the car has received over the years.

Oh, and while the 240Z was offered with an automatic gearbox it was an option that most people shunned at the time. You should too.

What to pay

For a while it looked like the price of a Datsun 240Z was only going one way – and quickly, at that. Yet the rise seems to have softened in recent months, which is bad news if you’ve got one but very good news if you’re still humming and hawing as to whether to buy one.

The entry price for a rust-free, left-hand-drive, automatic project is well under £10,000 with running restorations starting at about £12,000. Good 240Zs go for £20,000 and exceptional examples can reach £40,000 or more.

That seems like very good value to me given their rarity, exclusivity, performance and the sheer chutzpah they’re going to endow your life with.

A statement of intent

We are used to car manufacturers telling us what they’d like to do these days, a piece of marketing flim-flam that is usually accompanied by the unveiling of a wildly optimistic concept car that is little more than a cleverly disguised styling buck. Enthusiasts then wait a year or so with baited breath before feeling cheated when they see the watered-down production version, which is always a pale imitation of the show car that has been diluted and homogenised to meet the needs of a series of multi-cultural, multi-generational focus groups.

Which is not at all what happened back-in-the-day. No, back then, car manufacturers actually created something – and let the product do the talking. So, the Datsun 240Z was a statement of intent on behalf of the entire Japanese car manufacturing industry, setting it as serious competition for the lack-lustre (and hugely complacent) Europeans automotive industry. No longer could they sneer at the cars that were coming in from the far-east – or dismiss the fledging Japanese car industry as good for nothing other than building carbon-copy cheap shopping cars.

The Datsun 240Z was a klaxon call that alarmed the whole of the west and set the Japanese up as proper engineers as well as a nation that should be feared and respected in equal measure.

Carlton Boyce