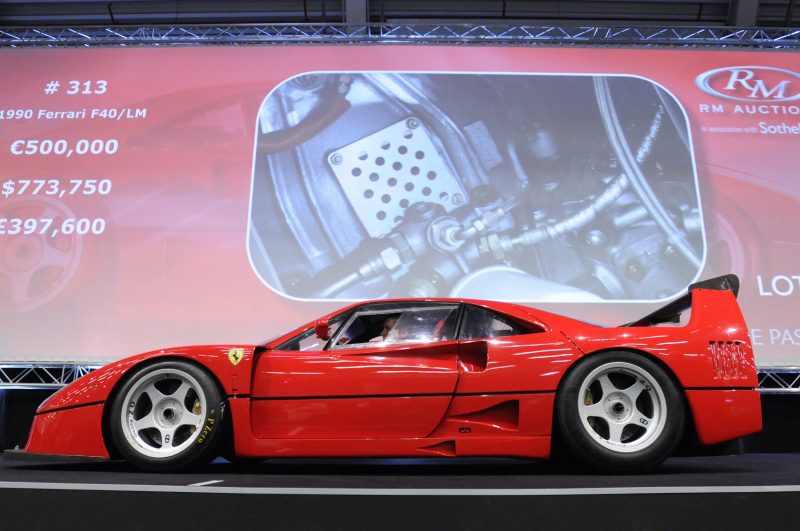

The Ferrari F40 was possibly the first supercar in the world for which less meant more. Or, if you are of a more cynical mindset, the first supercar that demonstrated that supercar manufacturers could take the piss out of their customers and get away with it.

Sure, as the first production car to break the 200mph barrier it was fast, but speed isn’t everything as the Bugatti Veyron so convincingly proves. Sure, it handled well, but not half as well as a Lotus Elan costing a twentieth of the price. Sure, it was exclusive, but then any car that doesn’t have a carpet, door trim, door handles, a stereo, carpets or a glovebox bloody well deserves to be. Especially when it cost £163,000 back in 1987.

Not that you could actually buy one for that; the demand for them was so high that by 1990 dealers made an art form out of taking the piss by charging twice the screen price to gullible customers that couldn’t bear to be without the latest must-have Ferrari. (Not to be outdone, Nigel Mansell did the same with his…)

This was, let us not forget, what rich-but-impotent self-medicated with before the invention of Viagra.

I am, of course, just jealous. (Of the F40, not the impotence.)

Technology laid bare

Because the F40 was a tour-de-force, a technological marvel and the last hurrah of the pre-digital age. If the McLaren F1 is the greatest car ever built, the Ferrari F40 is the greatest road-going racing car ever built.

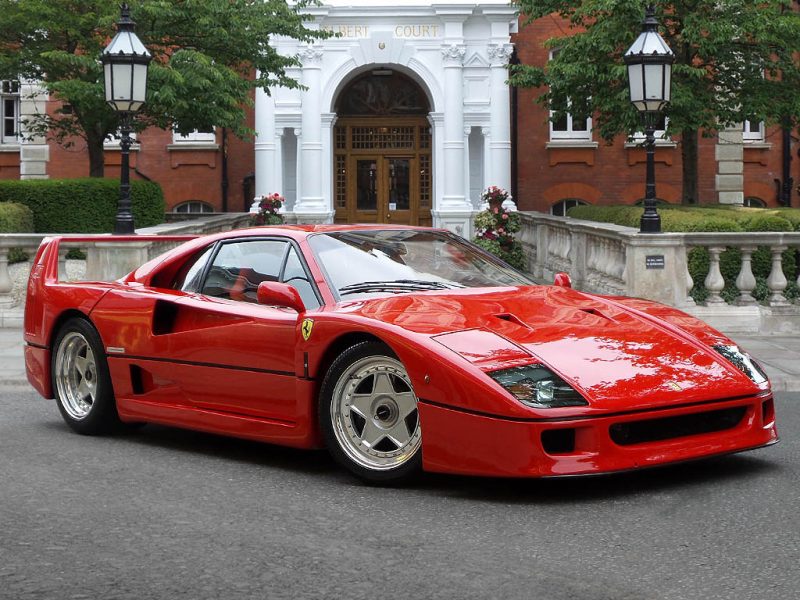

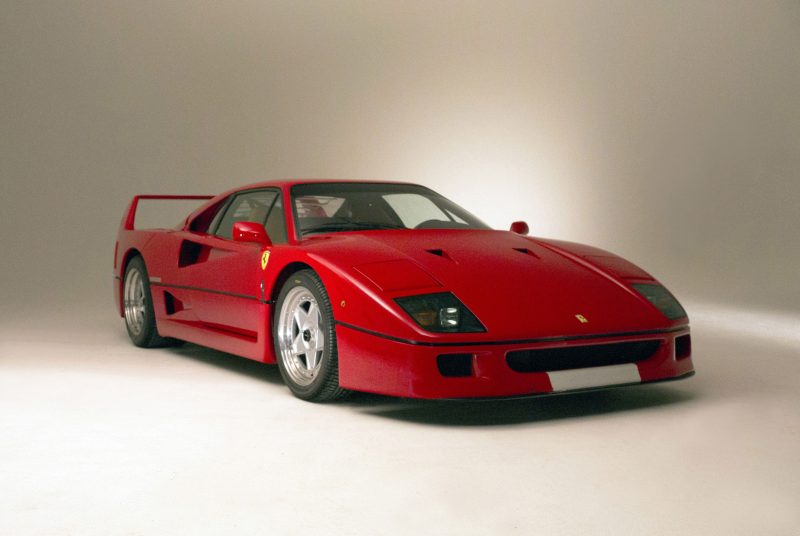

It starts with the way it looks; the F40 managed to steal the Lamborghini Countach’s thunder by being simultaneously delicate and brutal, beautiful and beastly. It’s the automotive equivalent of sharing cocaine with Grace Jones; arousing and intimidating in equal measure.

That low nose shovels air out of the way, and the myriad scoops and holes and ducts swallow what little doesn’t move out of the way fast enough. The rear spoiler has a greater surface area than my first London flat and the Pirelli P-Zero tyres display more rubber than John Holmes’ condom collection (unused, of course).

As for colour, some say that the F40 was only ever available in Rossa Corsa red but, as is so often the case, the truth is more complex than that.

It is true that most were red, but at least nine yellow F40s were delivered plus a few in black. Almost everything else was resprayed by Pininfarina, which was a good move as they designed it in the first place.

Oh, and there was so little paint used – some say as little as 2-litres for the whole car – that the carbon weave can be seen through it. This was a weight saving measure, and just one small step towards attaining the F40’s eventual 1,104kgs weight.

Probably saved Ferrari a few quid too.

The interior

Opening the door sets the tone for the rest of the car: the pedals are simple drilled metal; the roll cage’s door bars obstruct your entrance; and the only colour comes from the flame resistant material used to cover the barely padded racing seats, seats that could be ordered in three different widths: small, medium, and American.

But please don’t let me give you the impression that there is a retro, technological cool to the interior, because there most certainly isn’t. The joints between the bare Kevlar panels are sealed with a bead of lurid green jointing compound and the dashboard is covered with grey flannel, ostensibly to cut down on reflected glare. It is race-car purposeful rather than McLaren F1 interesting; no one at Ferrari thought to ask NASA to post them a roll of gold foil, for example.

This may well have been deliberate: not fitting stuff made the F40 considerably cheaper to build than it might otherwise have been.

Of course, it’s not all penny pinching because there are flashes of brilliance, too: the traditional metal Ferrari five-speed gear-lever gate is present and correct and looks as wonderful as ever; the steering wheel is small, flat-bottomed and black and covered with suede, all the better to stop your sweaty little mitts from slipping; and the red stripe at twelve o’clock – a somewhat vulgar touch in a Vauxhall Corsa but wonderfully evocative here because, well, F40 – helps you work out which way the steering wheel is pointing as you powerslide around Ascari. Or your local Tesco’s car-park in the snow.

The early cars also featured sliding Perspex windows, while the later models had normal, wind-up jobbies like those found on lesser cars. So everyone wants an early car. Obviously, because more Perspex equals more cool.

The chassis

The extensive use of carbon-kevlar in the construction of the bodywork meant that the F40’s bare shell weighed more than 500lbs less than that of its arch-rival, the Porsche 959. Not that that was ever a realistic comparison because they were two very different cars.

As a Ferrari spokesman explained: “We wanted it to be very fast, sporting in the extreme and Spartan. Customers had been saying our cars were becoming too plush and comfortable. The F40 is for the most enthusiastic of our owners who want nothing but sheer performance. It isn’t a laboratory for the future, as the 959 is. It is not Star Wars. And it wasn’t created because Porsche built the 959. It would have happened anyway.”

Where the engineering behind the 959 was a futuristic, the F40’s chassis was as uncompromising and as stark as its interior. Of course, they did use some technology but only sparingly and never unnecessarily. Which means there is no power steering, no brake servo, no anti-lock braking system, and absolutely no traction control.

Like the McLaren F1 and the Honda NSX, you have to drive a rear-wheel-drive F40 properly, or you will crash. Which is exactly how it should be.

The engine

If old man Ferrari skimped on the interior, he did, at least, splurge some of his savings on the 2.9-litre, all-alloy V8 engine. State-of-the-art at the time, its 478bhp power output might not sound like much now but its feral howl and almost instantaneous power delivery – thanks in no small part to parallel turbochargers – make driving one more about the experience than the power.

The fuel injection system is sequential and the twin turbochargers boost to 1.1 bar rather than the 0.85 bar of the 288 GTO Evoluzione upon which the F40’s engine was based. Enough power is never enough, not at Maranello. As Enzo himself used to say: “I don’t care if the door gaps are straight. When the driver steps on the gas, I want him to shit his pants.”

It’s clever, too. The con rod bushes are sliver/cadmium, and the crankshaft itself is ducted to help lubrication at high revs. All 32 valve stems are hollow to save weight and increase the engine’s responsiveness.

As a result, this is not a slow vehicle; the featherweight F40 can reach 62mph in well under four seconds, which is good going, even now.

Enzo was so proud of the F40’s engine that he presented it via a clear Perspex engine cover (more Perspex equals more cool, remember?). With louvres set into it, obviously.

While some of the packaging on the F40 might seem parsimonious, the engineering is carefully and thoughtfully wrought. That Ferrari is, at heart, a racing team was never more obvious; there is genuine beauty in the way the F40 is assembled, so why wouldn’t you want to show it off?

Driving an F40

Who knows? I’ve never driven one and am unlikely to ever be invited to do so. Others, cleverer and more talented and better connected than I, tell me that it is absolutely awesome.

The motoring press is full of brave stories, boldly told. Muttering Rotters speak of wilful handling, vicious lift-off oversteer, and mind-shattering levels of NVH. They talk of battling to tame a car that fights you every inch of the way until you finally wrestle it into submission, after which you have to slap it around every now and then, just to remind it who’s in charge.

But then you knew that. Didn’t you?

But motoring journalists, as I know better than most, can talk utter rubbish sometimes. The reality is, I suspect, more prosaic. I expect it feels very fast but heavy to drive. I’ll also bet that the suspension feels a bit soft by modern standards and the brakes are agricultural and barely adequate.

It probably feels, in in other words, a bit like every other old supercar ever made.

Production

In total, between 1,311 and 1,315 (the exact number is unclear) were built between 1987 and 1992, a figure that was way more than the 200 required for homologation and the 3-400 that were originally planned.

And yet, even this was someway short of the 3,000 that would have been needed to satisfy the number of potential customers that bombarded their local dealer with deposit cheques. But if they’d completely satisfied demand, they’d never have been able to charge over-the-odds, would they?

Buying one

If you’re buying one you really don’t need me to advise you. (For the gullible, my daily rate is available on request…)

For the rest of us, buying an F40 is an exercise in futile day dreaming, so why shouldn’t we indulge in a little fantasy fault-finding while we’re at it?

The car you want is an early, sliding window, non-cat, non-adjustable suspension car in original condition. American cars are cheaper, but are slower, heavier and just not as desirable. Unless they’ve been retro-spec’d as European cars, in which case they won’t be original so they will still be worth less than the model everyone wants.

As for pre-purchase checks, the fuel for the engine comes courtesy of twin rubber fuel bladders with a total capacity of 31.7 gallons. They need replacing every ten years at a cost of £5,500. Plus 20 hours’ worth of labour to fit them. Plus VAT. So you might want to make sure they’ve been replaced recently or budget accordingly.

The tyres need replacing every two years and probably can’t be found at your local Kwik Fit. Still, even their £2,000 price tag looks reasonable against the £32,000 it will cost you to buy (‘buy’, mind you, not ‘buy and have fitted’) a new front clamshell. Ferrari F40 owners view car-parks and sleeping policemen with equal caution.

You’ll need to budget a low-five figure sum for your annual service. Unless things start to go wrong, in which case your best bet is to hide under the duvet in the hope you’ll wake up to find it’s all just been a horrible dream.

Conclusion

The F40 came at just the right time for the Italian company because Ferraris of the 1980s were a bit rubbish and in dire need of an image boost, something the F40 did very well. Enzo might have died a year after its launch, but the F40’s legacy is such that it pointed Ferrari back in the right direction; hereafter, stripped-out and highly profitable ultra-high performance cars formed the backbone of the company’s portfolio, alongside branded clothing and aftershave, of course.

And the appeal hasn’t waned. Prices are rising, and rising fast. You can still buy one for under a million, but only just and probably not for long as our F40 Price trend shows.

Carlton Boyce