In a previous life I worked with a sixteen-year-old and I can never forget the look of mutual horror when I discovered that she had never heard of Don McLean – or hers when she realised that Madonna hadn’t written American Pie. Similarly, I’m sure there are folk out there who don’t realise that the current Morgan 3 Wheeler is merely the current incarnation of a model that stretches back well over a century. And because the Internet is stuffed full of gushing reviews of the modern car, so we’re going to take the time to go properly vintage and take a look at the original that inspired it too.

The modern car in a form in which we would recognise it was invented well over a century ago but it remained a luxury that was utterly unattainable by anyone other than the very, very rich until the 1930s. Until that point the working man had ridden either a horse, a bicycle, or he built himself a cyclecar.

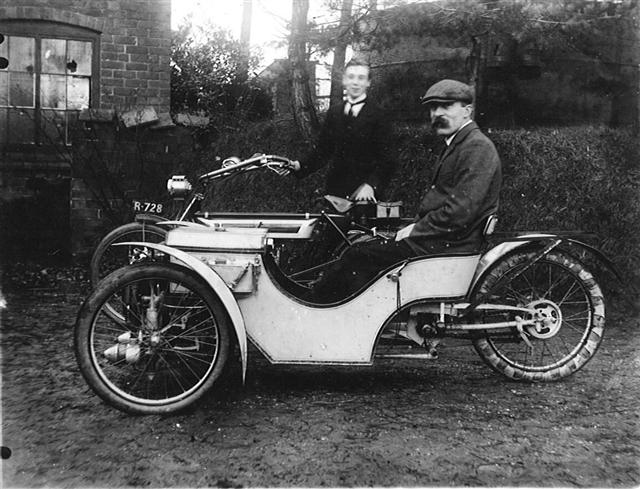

Constructed almost entirely of wood and bits of scrap metal, the cyclecar was a three- or four-wheeled contraption that straddled the hinterland ‘twixt car and motorcycle. Frequently built in sheds, their rein lasted a modest twenty years or so but the thinking behind them spawned a huge number of properly engineered production cars, not least the Morgan Super Sports.

Henry Fredrick Stanley (or H.F.S as he is widely known) Morgan opened his first garage in 1906 at the age of 25, running a local bus service using the Wolseleys he had the franchise to sell. Despite being so successful at such a tender age, life couldn’t have been as easy as appearances might have led his contemporaries to believe because old HFS had to build himself a cyclecar to get around in; his first three-wheeled chassis hit the road three years later.

The front suspension was the infamous ‘sliding pillar’ design that is still used on modern Morgans today, supporting a tubular steel chassis and a simple sheet-steel body supported by a wooden frame (sound familiar?). The design was, so far, neat but hardly the stuff of legend.

However, the propshaft ran through the central backbone of the chassis and the engine vented its exhaust gases through two of the four chassis side-members. These were just two examples of the sort of lateral thinking that HFS was so good at. As a result, the single-seater drew rave reviews from other motorists. So HFS took another leap in the dark and put it into production a year later thanks to a loan from the Bank of Dad. It remained in production, more or less unaltered, for the next forty years.

Early cars had just two forward speeds with reverse being provided by the driver hopping out to push, no hardship with a car that weighed as little as 350kgs. (The modern Morgan 3 Wheeler, by comparison, weighs a positively porky 525kgs.) Powered by either a 4hp single-cylinder or an 8hp J.A.P. twin, steering was by way of a tiller and while the crash and weather protection was almost non-existent, driving one kept the driver a little bit drier than he would otherwise be on a horse or motorcycle. And anyway, we drive what we drive for reasons other than practicality and the little Morgan was a sensation in its time.

Especially when it gained another seat; the combination of the larger J.A.P. engine and the ability to carry a passenger proved irresistible and Morgan sold 30 at its debut at the Olympia show. Dashing young men – and some of them were very dashing indeed. Morgan’s marketing department would have loved the fact that two British fighter aces, both of whom were awarded the Victoria Cross, drove Morgans when they weren’t shooting Jerry – could now carry their sweethearts alongside them, secure in the knowledge that their wheels were developing a real pedigree; H.F.S. was already racing them very successfully and the ‘Win on Sunday, sell on Monday’ mantra was already being proven.

Competition has always been at the heart of what Morgan does, and the Super Sports three wheeler was astonishingly accomplished and held the road far better than anything with only three tiny patches of rubber could be expected to. Drifts came as standard (with just 8 imperial horsepower, remember?) and the little trike proved to be a giant killer half-a-century before the Mini made small competition cars cute.

A four-seat model – quite possibly a Top Ten contender in the Ugliest Cars Ever Made competition, although the Morgan van that was its contemporary, runs it close – came along in 1915.

The end of the war saw three models being offered but while the rest of the United Kingdom was suffering under the post-war economic depression that had kicked in with a vengeance (and we would remain economically and socially depressed for the next twenty years), Morgan was kept busy building 129 cars a month and while accurate sales figures are hard to come by, it is fair to say that the modern 3 Wheeler isn’t selling in anything like these numbers.

The mass-market, low-cost Austin Seven might have killed the Morgan but for a very clever marketing strategy that placed the Morgan as the low-cost, sporting alternative to the staid, sensible Austin. It was a clever move; I mean would you rather have the reputation as a steady family man that buys an Austin, or the sort of devil-may-care, VC-wearing chap that shoots down Huns before breakfasting on a pint and a local wench?

Quite. Which is where the modern Morgan 3 Wheeler comes in. It brings the engineering (almost) slap-bang into the 21st century while evoking fight-plane fantasies by way of bullet-holes, Union flags, RAF roundels, and glamorous cartoon women. It is unashamedly British, conjuring up warm beer, the gentle thud of leather on willow, and sheepskin flying jackets.

Which is appropriate, really because the performance is lukewarm, the slightest accident will have you experiencing the gentle thud of your own leather on the ash-frame, and you’ll need some form of protection to keep you safe from the dual ravages of the elements and gravel rash.

Of course, I’m joking. Kind of.

Performance is rather stronger than lukewarm and a 0-62mph time of around six seconds is decent enough, although only the brave or the foolhardy would attempt to explore the upper reaches of the 3 Wheeler’s 115mph top speed. However, the fact remains that crash protection is just about non-existent although the modern car will, just like its ancestors, keep you slightly drier than a motorcycle would.

But the 3 Wheeler is, just like every Morgan ever built, bought by those with an eye for the past and a nod to every VC who has ever driven one. Often benchmarked as the nearest thing to flying without leaving the ground, the Morgan fairly flied along thanks to its almost scarily scant weight.

Of course, the impracticalities aren’t limited to a sub-zero NCAP score; the official fuel consumption figure of 30.3mpg is likely to prove aspirational rather than achievable and the CO2 figure is a whopping 215g/km, which really isn’t good enough for such a light car.

Tall and/or fat blokes need not apply, either but if you can fit in – and are happy to donate your own extremities as the crumple zones of your £30,000 car – then you’re in for a treat. The S&S engine throbs away most convincingly and the Mazda MX-5 gearbox is as sweet as anything this side of an NSX. Throw in telepathic handling and some of the most easily controlled slides in the business and you’ll start to understand why the world has gone bonkers for the 3 Wheeler.

Which means the introduction of the EV3, a three-wheeled Morgan powered by an electric motor, is cause for even more celebration. No trike is never going to be a practical everyday proposition, so the EV3’s more limited range is likely to be less of a bar to ownership than it might otherwise have been.

The extra weight of the batteries might be problematic (Morgan claims that the all-up weight will be “under 500kgs” but the skeptical might was to make a note of what the production car weighs when it hits the showrooms) but the near-silent and instantaneous torque delivery should make the EV3 a complete hoot to drive.

The EV3’s asymmetric three-headlight frontal treatment adds another layer of quirkiness to a car that is already more eccentric than the Marquess of Bath enjoying afternoon tea in a bath of raspberry jelly with Björk stroking a well-oiled otter at the tap end.

I want one, and so do you.

Production is scheduled to start in 2017 and the cost is likely to be around £40,000, which is a far cry from HFS’s tiller-steered cyclecar, eh?

Carlton Boyce