The Ford Escort MKI might have remained an uninteresting footnote in Ford’s back catalogue were it not for its competition success. Despite having little in common with the production Escort bar the bodyshell, the reflected glory of legends like Roger Clark, Tony ‘Top Gear’ Mason, and Hannu Mikkola meant that every man wanted one on the driveway; in sporting circles the little Ford Escort punched so far above its weight that even Muhammad Ali wouldn’t have taken it on.

Mind you, even the most basic road cars went well. Launched in 1968, the first cars weighed just 767kgs, even the smallest engine – and with just 900ccs, some of the engines were very small indeed – gave enough performance to keep drivers who were used to the barely mobile family cars of the 1960s very happy indeed.

They quickly discovered that the Escort was a nicely balanced car too, with decent weight distribution, a snappy gear-change and terrific handling. Neat looks too, with the sort of quasi-American styling that instantly endows any car with worldwide appeal, even three-box saloons, albeit one with the now classic nipped-waist, Coke bottle profile.

The mechanical formula is a familiar one now, so it’s hard to understand how groundbreaking it was at the time. We now (correctly) interpret rack and pinion steering and Macpherson strut front suspension as the sort of commonplace fodder foisted on a car by accountants rather than engineers but on the Escort they were transformational. The Escort mobilized the working classes and proved once and for all that an affordable car didn’t have to be a bad car.

The Escort wasn’t just a nifty piece of engineering to drive. It was tough, so tough that a career in long-distance, endurance rallying was inevitable and to say that the Escort dominated whichever class it competed in is to understate that dominance. The Escort, in all its incarnations and across the generations, is the most successful rally car of all time and remains competitive at club level even today.

The first street-legal fast Escort was the Lotus-engined Twin Cam. Developed on something less than a shoestring, the Twin Cam was essentially an Escort body sitting astride the oily bits from a Lotus Cortina. Despite little development, the Twin Cam was a brilliantly balanced little car with enough performance to embarrass cars costing twice the price.

To keep costs down and to make them affordable for even the most cash-strapped race teams they were all painted white. The interior trim was somber and basic and came only in Henry Ford’s favourite colour. They also had the battery and spare wheel in the boot for perfect balance, something contemporary road testers complained about as it left little space for luggage, which misses the point, surely.

With 109bhp, the Twin Cam topped out at 100mph and hit 60mph from rest in under ten seconds. It was a sensation but only 1,000 were ever built in order to satisfy the FIA’s homologation requirements. Well, that’s what Ford claimed; enthusiasts suspect that as few as 883 might actually have left the factory…

The legendary Cosworth-tuned RS1600 debuted in 1970. Powered by a 16-valve BDA (Belt Drive, Series A) engine squeezed into a fully seam-welded bodyshell, the Rallye Sport had a top speed of 113mph and rest-to-sixty acceleration of just under 9 seconds courtesy of 115bhp and 110lb/ft of torque. With the exception of the engine, it was almost identical to the Twin Cam that preceded it but when you’re onto a winning formula you’re not going to worry too much about accusations of laziness especially given that the works cars finished up with a gargantuan 250bhp.

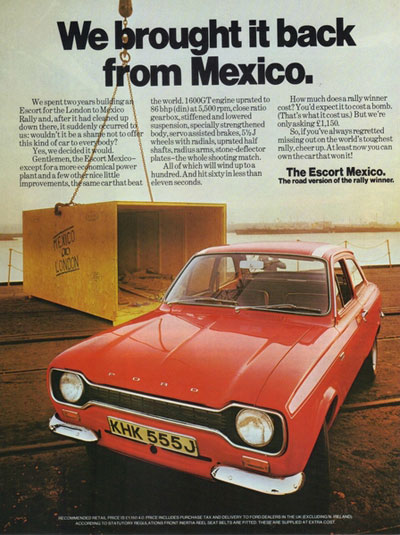

The RS1600 was closely followed by the Escort Mexico of the same year. Named after the Hannu Mikkola’s 1970 London-Mexico rally win the Mexico was essentially an RS1600 with a more conventional – and much cheaper – 1600cc ‘Kent’ four-cylinder engine. Eighty-six bhp wasn’t really enough, and performance was distinctly pedestrian at 99mph and 10.7 seconds to 60mph. Interestingly, four Mexico estates were produced, making it possibly the first car to feature the road test cliché of a Labrador in the boot that failed to enjoy its owners enthusiasm for driving fast along twisty country lanes. The Mexico was a reasonably mainstream car and stayed in production until 1975, when it died with the rest of the MKI range.

The RS2000 arrived (sideways, I suspect, and in a cloud of tyre smoke) in 1973. Fitted with the two-litre ‘Pinto’ engine it was said to be a less temperamental and more reliable alternative to the more brittle and highly tuned engine of the RS1600. As such, it was something of a bridge model between the fast-and-fragile RS1600 and the tough-but-slow Mexico. It came with wide, go-faster stripes down the sides, bonnet and boot although more subtle pinstripes were a no-cost option. The cars came with steel wheels as standard but four-spoke alloys were practically compulsory.

Power was slightly down on that of the RS1600 at 100bhp and 107lb/ft of torque making it a fair bit slower as well as more numerous; it’s thought that around 5,300 were built in total, easily satisfying the requirement for 5,000 that were needed for homologation purposes. The United Kingdom accounted for the bulk of those sold with about 3,500 being registered to British buyers.

More pedestrian cars were available, of course. The Escort was a family car par excellence and four-door and estate versions ruled the roost on driveways across the land. Ford played on the competition theme mercilessly selling all manner of variants that hinted at the model’s racing and rallying pedigree without having a commensurate price tag.

Many will now have been converted to a more sporting specification but an Escort estate with its original paint and with all of its trim intact would make a fine addition to any collector’s garage.

Of course, originality is all very well but I’m willing to go out on a limb and say that no car looks better with flared or boxed arches than the original two-door Ford Escort. Lower the suspension and bolt on some wide alloys sheathed with low-profile rubber and you’ve got a very cool car indeed. Dial in a roll-cage and some bucket seats topped off with a deep-dish steering wheel and a pair of four-point harnesses and you’ve got possibly the finest set of wheels this side of a Singer Porsche 911.

Speaking of which, if you thought that the price of Porsche 911s and even Ford Capris was bonkers (and, frankly, you’d be mildly insane to think otherwise) then you obviously haven’t seen the price of early Ford Escorts. Two-door body shells (rusty body shells at that) are being advertised for, and changing hands at, £7,000+.

Concours RS models sell for £50,000 and more, while competition cars without provenance are selling for six figures – and a decent competition history will double that.

Which is obviously bonkers. So my buying advice is to take a look at the next rising star and buy a MKII.

But you’re not going to do that, are you? In which case you need to take a long hard look at the paperwork and take a nerdy approach to the little details on the car itself to decide if the car is genuine; few cars are easier to fake that the RS models, so you need to be certain that you are buying the car you are paying for.

I’d also want to see signs of obsession, so several thousand photographs of the rebuild would do a lot to reassure me that the guy knew what he was doing. Having said that, the Escort might be one of the few cars that breaks the almost immutable rule that you should always let someone else pay the restoration costs. With the mechanical components comprising such a tiny fraction of the overall rebuild costs (Louts twin-cam engine aside), the bodywork is going to suck up the bulk of your money, no matter what, which might make even a rust-blown bodyshell worth considering, although I’d baulk at paying seven grand for one.

More than two million MKI Escorts were built and a surprisingly high percentage have survived. It’s thought that several tens of thousands survive, so there are plenty out there, even if their owners are asking all the money.

The Escort still feels surprisingly modern to drive, especially the faster models where the available performance makes up for period brakes and a suspension compliance that Audi would be proud of. The initial ‘rightness’ of the car is evident within a few miles and it is easy to see how it beguiled an entire generation so living with one would be easy. As long as you’ve got deep pockets to buy one in the first place, of course.

Carlton Boyce