The legacy of the McLaren F1, even now, cannot be overstated: “without it, we wouldn’t be here today” as one McLaren Automotive engineer put it to me. Of course, its towering performance is the headline act but this level of innovation, obsession, engineering and sheer genius will never been seen again.

It couldn’t be. Not now, not ever. In a world now ruled by accountants and health-and-safety legislation and the need to be seen to be responsible, it simply couldn’t be.

But back in 1988 the world was so benign that someone like Gordon Murray could pitch the idea of a three-seat supercar to Ron Dennis in an airport lounge with a rough ‘n’ ready sketch. That Ron said yes wasn’t a surprise. Gordon was, back then, merely an automotive demi-God, and demi-Gods are prone to boredom and to complacency. Gordon’s cars ruled the rarified world of Formula One but there was an itch that he had yet to scratch, an itch that had been building for a lifetime. If Ron had said ‘no’ then Gordon probably wouldn’t have left McLaren but he might have done and that was enough to persuade Ron to give him free rein, to indulge him, to let him scratch that itch in a McLaren workshop. The fact was that McLaren needed Gordon more than Gordon needed McLaren.

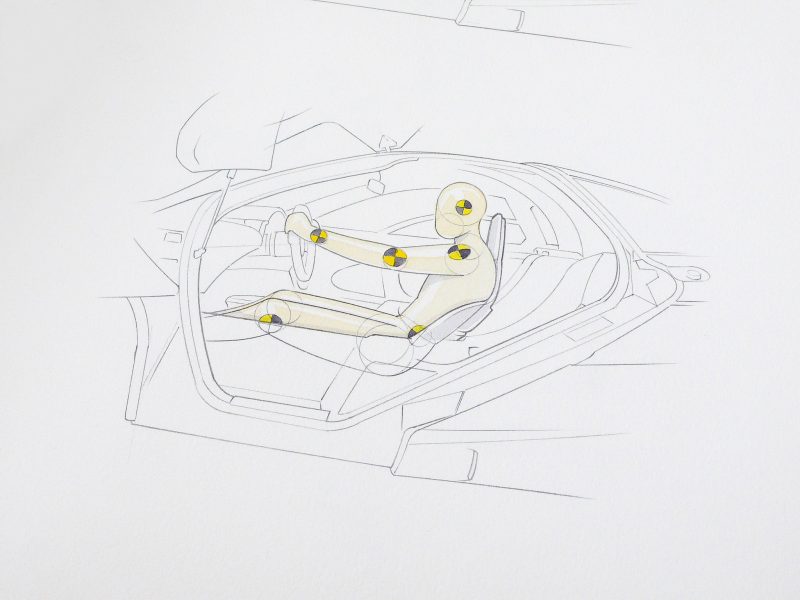

A central driving position would be unconscionable now, but back then it was the key to Gordon’s dream. It was the answer to a question that no one had ever thought to ask. It allowed for perfect packaging, compact dimensions, and as much luggage space as anyone would ever need. It made, in short, perfect sense so Gordon made it happen.

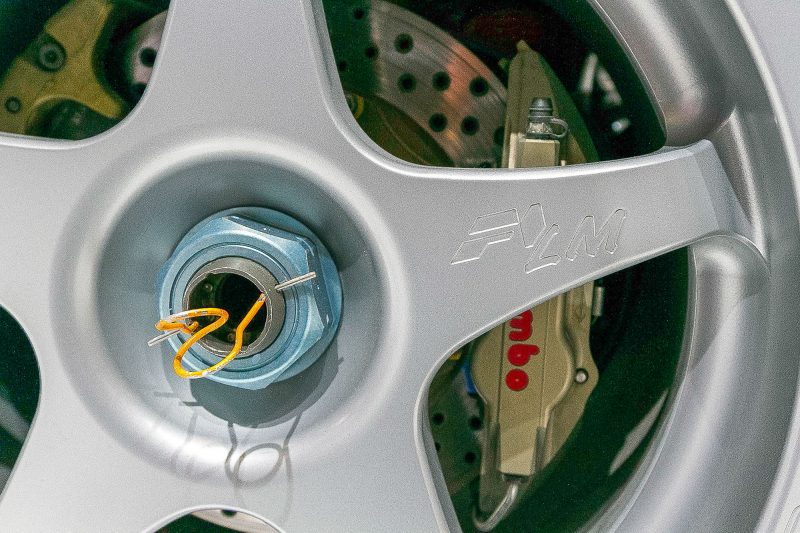

Gordon also ignored the sort of received wisdom that everyone else accepted without question. Take braking, for example. Anti-lock brakes saved lives so everyone was in a rush to fit them, ignoring the fact that they also add weight and complexity and dilute the driving experience. These things mattered to Gordon, and he trusted that the sort of people who would buy his car would know what they were doing, so he didn’t fit them. After flirting unsuccessfully with composite brakes he eventually settled on a quartet of huge cross-drilled steel discs, clamped by the most exquisite one-piece, four-pot Brembo calipers you’ll ever set eyes on. Of course, you don’t need me to tell you that there was no servo assistance.

Nor did Gordon fit a radio, simply because he never listened to one. And when the chaps from Kenwood came to Woking to tell him that it simply couldn’t make a lighter in-car entertainment system, Gordon stalled them (he was trying to explain why he didn’t need a separate balance control without giving away the fact that his still-secret car was going to have a central driving position) and after an hour he returned the amplifier that the guys from Kenwood had brought with them; he had had it machined and pared down by the Formula One guys, just to prove that it could be done.

Because Gordon isn’t the sort of bloke to accept ‘no’ for an answer. This probably made him a bit of a pain to work for but his team loved him, mainly because they were a team. He gathered together a number of cars for benchmarking including a Porsche 959 (“technologically interesting but very sterile” apparently) and Nick Mason’s Ferrari F40, and made sure to take everyone out for a spin to help them understand exactly what he was thinking. And by everyone, I mean everyone; even June the tea lady went along for a ride.

While Gordon benchmarked some of the world’s best and most expensive cars he didn’t copy them. There was simply no point because nothing was as good as the car he wanted to build.

Well, nothing until the Honda NSX, which blew Gordon’s mind. The NSX’s ease of use, ride, handling, perfect visibility, heating and ventilation, and rifle-bolt gear-change became the new benchmark (rumour has it that the F1’s gear linkage bears an uncanny resemblance to that of the Honda…). He even ran one as his company car and loved it.

Interestingly, the McLaren F1 still holds its own, even now and even within the company itself. The designers at McLaren Automotive still turn to the F1 for inspiration, gathering around one of the three that sit on The Boulevard at the McLaren Technology Centre in Woking, coffee in hand to see how Gordon and his team solved a similar problem all those years ago.

Mind you, the problems might be similar but the lack of legislation and the F1’s an unlimited budget meant that problem solving was much easier back then. Take the 6.1-litre, 48-valve, V12 BMW engine, for example. It produces incredible power – upwards of 627bhp and 480lb/ft of torque – and revs to 7,500rpm. As a consequence, it produces an incredible amount of heat but that’s OK, because when your budget is unlimited you just call NASA and order a few rolls of gold foil to use as insulation.

The world’s best hypercar would need an extraordinarily light yet stiff chassis, so it was only natural that Gordon’s outfit would turn to the Formula One team for help; the McLaren MP4-1 of 1981-83 was the first Formula One car in the world to have a Carbon-Fibre-Composite (CFC) monocoque chassis, an engineering innovation that set new records at the time for torsional rigidity and driver safety. The team’s expertise was to prove vital and the McLaren F1, with its 48-piece bodyshell, became the first road car in the world to have a carbon composite monocoque – and it has the patents to prove it.

And when you need to install attachment points for the engine, gearbox and suspension, it makes perfect sense to use magnesium and aluminium. Anodized, of course, even in the areas the owner will never see because it’s just as important to delight and surprise the servicing technician. “Little bits of jewellery” as one of the designers put it to me to explain the gold and purple anodized finish that crop up throughout the car under service hatches and behind the trim.

Or when you need to fit a toolkit but want to keep the weight as low as possible (the target was 1,000kgs, which might have been missed but it wasn’t missed by much) you simply pick up the phone to Facom in France and order a set in titanium spanners at half the weight and about £1,000 a pop, in case you’re interested. You also shave the Connolly leather to a mere 0.7mm in thickness, a move that might save you a few hundred grams, but a few hundred grams here and there soon adds up to a kilogram, and a kilogram is a weight that is well worth saving.

The exhaust system is an interesting example of the kind of lateral thinking that went into the F1. Built of an Inconel/titanium alloy and reputed to cost the same as a very nice terraced house in a Northern town, it is less than half the weight of a steel system and doubles up as a crumple zone in the event of a rear-end accident. That it is heart-achingly beautiful is a byproduct of great engineering rather than conscious design.

The washer fluid cap, like the oil filler and radiator caps, is machined from alloy when everyone else was using off-the-shelf plastic parts. McLaren also blazed a trail by fitting a modem so problems could be diagnosed remotely, another automotive first. (Interestingly, one of the biggest headaches of keeping the F1 road cars running is the diminishing availability of the kind of period computers needed to be able to run 25-year-old software.)

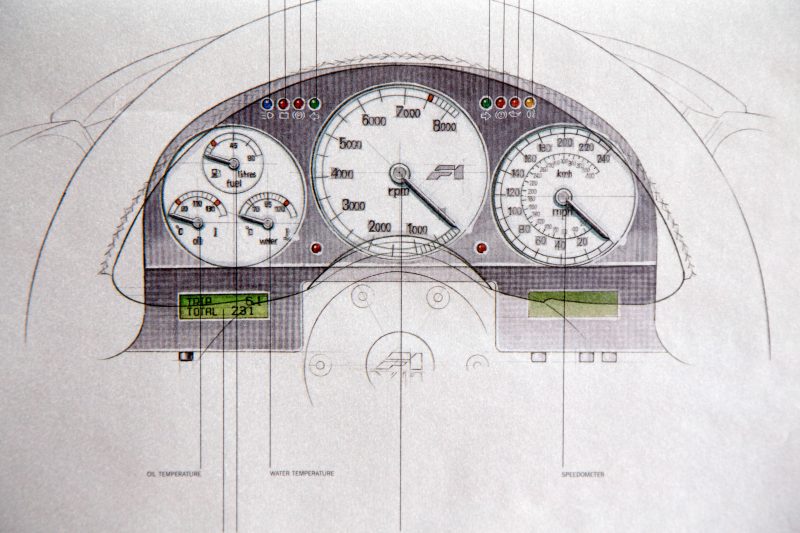

Even the handbook is a work of art. It cost £400 to print, even back then in the early nineties, and features the sort of utterly gorgeous line drawings that make geeks like me go weak at the knee. (I owned one once, but sold it for £1,600 to pay for a new gas boiler. It’s probably worth twice that now.)

Owners also got a unique TAG-Heuer watch, a Facom roll-cab toolbox and torque wrench, a McLaren F1 floor mat for the car to sit on in the garage, a full set of hand-crafted fitted leather luggage, and a scale model of their car finished in the same colour as the real thing.

Every single aspect of the F1 was designed to delight the owners – and to crush the opposition.

And crush them it did. A top speed of 240.1mph is still a world record, and if the 0-60mph time of 3.2 seconds has now been eclipsed the mid-range torque and furious noise are still very competitive. Unimpressed? How about the braking, which is ferocious enough that you can brake from 70mph to a standstill in just 49 metres? Or the 1.3G of lateral cornering force that it is capable of generating in the dry?

But drama isn’t mathematical, it is visceral and instinctive and organic, and that was Gordon’s genius. Peter Stevens might have designed the body but he simply draped carbon-fibre over the mechanical bits to produce a shape that looks contemporary now and probably always will.

Despite all this, the original planned production run of 300 cars was wildly optimistic. The £540,000 purchase price might look like a bit of a bargain now (current marker prices are £6,000,000 and rising quickly) but at the time it scared people off. Hard to believe, but there was an awful lot of arm-twisting involved back then to get anyone to even put a deposit down. People liked the idea of the car, but many weren’t convinced that the new guy on the block could deliver. McLaren might have been winning everything there was to win in Formula One but many doubted that even that level of racing success could guarantee that a road car would even emerge at the end, much less be any good.

McLaren might have shifted more if it’d made it clear to prospective buyers that each car was being sold at a loss, but McLaren is a proud company and isn’t given to begging, so only 106 cars were built in the end plus one spare chassis.

Of the 106 McLaren F1s, seven were prototypes, 64 were road cars, 28 were GTRs built for racing (although many ended up being converted into road cars after their racing careers came to an end), and five were Papaya Orange LMs designed to celebrate McLaren’s Le Mans victory, a race it won at its first outing, obviously. The final two cars are GTs, a road-going homologation special based on the racing GTR that was ultimately unnecessary.

The McLaren F1 was a far more practical car than you might imagine. It has the same luggage space as contemporary BMW 5-series thanks to custom-fitted luggage that included a full-size bag for your golf clubs. The three-seat layout makes perfect sense too, as does the compact dimensions and fighter aircraft visibility that make the world’s fastest naturally aspirated car uncannily easy to drive in the city.

Those who have driven one (sadly, I am not among their number, although I remain open to the possibility if anyone has one they’re feeling an urge to share) tell me that the suspension feels a bit soft by the standards of today but that the power and performance are as urgent and staggering as they ever were.

Of course, modern cars also have ABS and ETC and all manner of failsafe devices to make sure that it’s hard to overcook it in the first place and if you do manage to be a twat despite all that computing power you will probably be able to catch the ensuing slide with only a modicum of talent.

Which is not something you can rely on with the McLaren as it is utterly devoid of even the most rudimentary safety net. That same lax legislation that allowed Gordon so much freedom endows the driver with the same autonomy. So, if you press the throttle too hard, brake mid-bend, or do anything else without thinking it through very carefully, you will end up being spat off at a very high rate of knots.

Crashing aside, running one now is an exercise in profligate expenditure. As an example, the fuel cell needs replacing every five years, and with the exception of the door mirrors, which came from the Citroen CX and, later, the VW Corrado, and the Vauxhall door mirror switch, everything is bespoke and hand-fabricated. That makes almost everything on the F1 very light and utterly gorgeous but very, very expensive to replace.

Yet it is all still available. McLaren Special Operations, run out of an anonymous factory unit on an industrial estate a few miles from the MTC, still sells and fettles the F1, even now. Whether you want an interior re-trim, engine overhaul, or extensive chassis repairs (yes Rowan, I’m looking at you…) the guys at MSO are happy to oblige.

Seeing almost a dozen F1s lined up in various states of repair is a sobering sight, as is being able to see under the skin; the McLaren is a relatively simple car to maintain and the engineering integrity that flows though every inch of it ensures that everything is accessible. Servicing an F1 at home is, as Jay Leno demonstrates, just about possible.

If you want to dodge the main dealer and go aftermarket, there are people out there that can source and maintain a car for you. One McLaren F1 specialist told me that he knows of several cars that aren’t advertised on the market and never will be but are available, at a price. He asks for, and gets, a £1,000,000 deposit before he’ll even pick up the phone to broker you a deal but business is flourishing and I counted half-a-dozen F1s in his workshop when I last visited.

The rest of us have to make do with F1 memorabilia rather than the real thing. Apart from the aforementioned owners’ handbook, there is a flourishing trade in everything from random bits of bodywork through to press packs and limited edition books.

If you want to start somewhere then Driving Ambition, the official history of the McLaren F1, is a great place to start. It isn’t cheap but it is definitive, otherwise eBay is a rich source of odds and sods and still yields the odd bargain. I gaze at my own 1:18 scale model every day with a mixture of wonder and jealousy.

I will never own a McLaren F1, and that makes me sad. We will never see its like again, of that I am sure. But it exists, and there are enough owners out there who enjoy using them that anyone can go and see one in action and, if you pick your venue carefully, you’ll be able to see one up close.

Carlton Boyce