The Sweeney drove Ford Consuls and Granadas, which left the producers of The Professionals at a bit of a loss. They didn’t want to ape The Sweeney too closely but as fast cars seemed to have been an integral apt of the show’s appeal – alongside the fighting and shagging – they needed some wheels that would be as iconic and stylish as the two lead characters. They tried a couple of Rover SD1s alongside a TR7 and a Dolomite Sprint, but the vibe just wasn’t right – and even if it had been, the cars kept breaking down, which played havoc with the filming schedule. This will surprise no one who has ever owned or driven anything built by BL in the 1970s…

So they turned instead to the blue oval, sitting the enigmatic and extraordinarily grumpy head of CI5, George Cowley, behind the wheel of a Granada. But Bodie and Doyle were way younger, cooler, and hipper than Regan and Carter, so after flirting with the Escort they finally settled on a brace of Ford Capri 3.0Ss. Which was a bloody genius move and gave an immediate and sustained boost to the ailing Capri as well as the fledgling cardboard box industry.

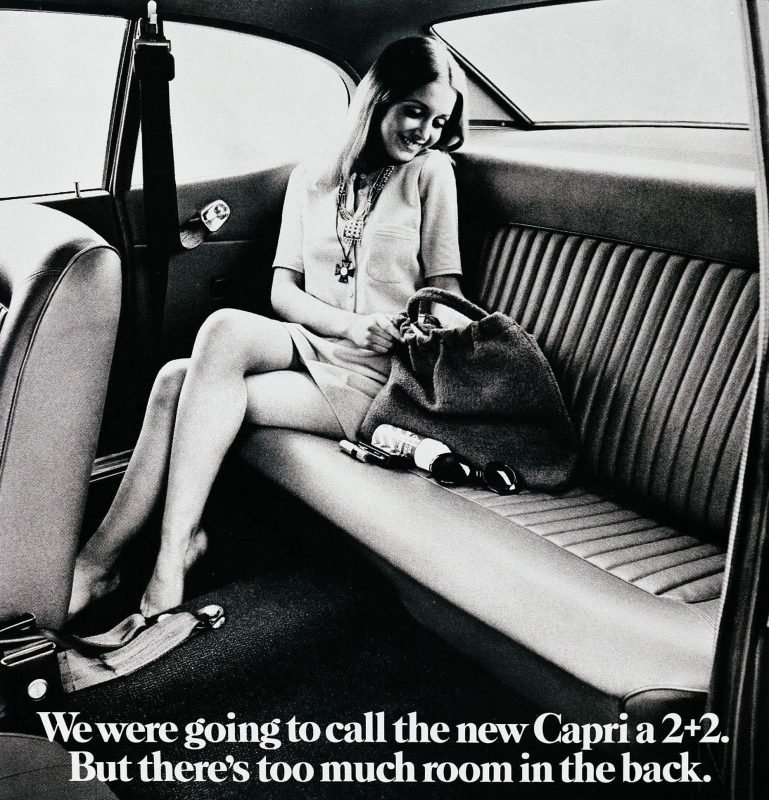

Billed as The Car You Always Promised Yourself, the Capri was launched in 1969. Heavily influenced by American muscle cars like the Ford Mustang, it trod a well-worn path by being based on the underpinnings of a much more mundane machine, in this case a Ford Cortina.

Despite this, it was an instant hit with reviewers and owners alike who forgave the rather crude chassis and underwhelming performance because it looked amazing and cost mere pennies. And anyway, performance could wait because the Capri was all about image and presence, of which it had both. In spades.

The impoverished public snapped them up, even those fitted with the lowly 1.3-litre engine, a powerplant that struggled to push the Capri past 80mph. (As for the acceleration, well, shall we just say that it’s leisurely, and leave it at that?) This was a fastback coupe in the American mould and it was called THE CAPRI. THE CAPRI! Accurate production figures are hard to come by but a company insider told me that the official term for sales in the first full year of production was ‘shit loads’.

We might sneer now at Capri being an exotic holiday destination but that’s because we’re spoiled; in the late 1960s only impossibly rich and glamorous folk holidayed in places like that, and if you couldn’t join them you could at least drive a car named after their playground, boasting of the fact to your neighbours as you sipped your Campari and soda while eating cheese and pineapple cubes that had been speared into a raw potato to form an edible hedgehog.

God, how simple and innocent life was then.

Which was just as well, because the Capri was anything but sophisticated. While power oversteer was never going to be a problem, lift-off oversteer was and many a Capri driver overcooked it on a wet roundabout, discovering that a live rear axle and cart springs was old technology and past its due date, even in the late 1960s.

Of course, the temptation to build a car with more power that you could charge more for was absolutely irresistible and the Capri eventually ended up with a range of high-performance engines under that long bonnet, including the legendary 2.8 and 3.0 V6s. South African drivers, meanwhile, could opt for a full-on, heavy duty 5.0-litre V8 that developed more than 200bhp as well as a soundtrack to die for.

The Capri did rather well in competition, too. The RS2600 and RS3100 both punched well above their weight, and sales rocketed as a result; the 1,000,000th Capri built was an RS2600 in 1973, coincidently its best-selling year.

Over the following years the Capri gained equipment, more trim levels, mid-range engines, better suspension and even an automatic gearbox, moving it from a car driven by working-class rebels to one driven by workday drones. It became mainstream and middle-class and watching one drive past became the equivalent of seeing James Dean behind the counter of your local bank in a cheap Burtons’ suit.

Nor were the years kind to the Capri’s waistline; it followed the trajectory of its owners gaining weight and size in equal measure. While early cars weighed well under 1,000kgs the last of the breed weighed around 300kgs more, even if they did produce rather more power.

The trouble was that the Capri’s looks simply weren’t enough for a customer base that was becoming ever more sophisticated. Once you’d actually visited Capri, you were unlikely to restrict your automotive ambitions to a car designed in Essex, were you? No, you’d turn your attentions to cars that were as exotic as your holidays, cars like the Alfa Romeo GTV and Saab 99 turbo. Cars that spoke your language, a lexicon filled with words like culture and aspiration and intelligence.

Of course, anyone who wore a shiny rally jacket with an RS badge on the breast was still content to wear their allegiance with pride but sales slumped and the Capri seemed doomed.

Until the advent of a new TV series called The Professionals; Ford had by now learned the power of having its products powersliding across our TV screens on a Saturday night, so giving the producers free rein to have as many of its cars as they needed was only sensible. Bodie and Doyle finally saddled up in matching Capris and one of the most enduring TV relationships was born.

The Capri was saved, for a while, at least.

Not that it lasted. The Professionals turned into a bad parody of itself and the Capri became the punch line to a bad joke. The Capri had been built in Germany since 1976 but even improved quality control and an association with a more glamorous country than England couldn’t resuscitate it. Production came to an end in 1988.

Now, with the benefit of almost 30 years of hindsight, the Capri isn’t judged as being such a bad car after all. I recently drove a 280 Brooklands (the run out model with the 2.8-litre, fuel injected V6 engine and the limited-slip differential) from The Great Escape classic car hire fleet and was surprised at just how good it was. Whining diff aside, it handled like a much newer car and performance was strong, if not actually rapid. The grey leather Recaro seats still give all the support you’ll ever need and the driving position is lovely, all stretched arms and laid-back demeanour.

It looked bloody wonderful too, squaring a circle that is now 47 years old and drawing attention – all of it positive – wherever it went. I came away wanting one very badly (although, to be fair, writing about old cars often ends in expenditure for me…). The shame is, for buyers, if not owners, that prices are soaring implausibly fast and improbably high.

Cheap, rusty projects might still be hovering at around the £1,500 mark but £40,000 isn’t unusual for good, early cars and higher prices aren’t unknown. One of the original Professional cars sold recently for £55,000, with Dennis Waterman’s Minder Capri selling for £52,500.

And, proving that provenance isn’t everything, a factory fresh Capri 280 Brooklands with just 936 miles on the clock recently fetched £54,000 and I suspect we’ll look back at that in the near future and wonder why it was so cheap. Of course, there are plenty of good, original cars on the market for £10-25,000 but there is also a lot of tat out there too, hastily blown-over in an under-the-arches bodyshop in the hope that an unsuspecting and naïve investor will sink his life savings into the Next Big Thing.

Obviously you’ll pay more for the sought after MK I and then prices aren’t rising as fast as they are for the MK IIs and IIIs which could prove to be a canny place for your money (data from Patina Price Trends).

With almost 2,000,000 built finding a good one should be easy. However, there are probably fewer than 2,000 2.8i Capris on either SORN or taxed in and in regular use in the United Kingdom and the total number of Capris that are worth saving is almost certainly under five figures in total.

This makes finding a good one quite hard. Your best bet is one of the many owners’ clubs as well as the usual online outlets but beware of rusty cars that have been tarted up to ride the current speculative wave; the bodyshell is more complex than it looks and terminal rust can be lurking almost anywhere under a thin skim of paint and filler.

So the bodyshell should be your priority, followed by any unique pieces of trim. The mechanical components are shared across most of the Ford range, so are easy to find, cheap to buy and straightforward to fit. As a result, you shouldn’t be afraid of buying a good bodyshell and then building one up yourself, providing that the paperwork is all in order.

And if you meet domestic resistance why not try reminding them that the Capri is The Car You Always Promised Yourself? If that doesn’t work, I’ve always found that it is easier to seek forgiveness than permission.

Carlton Boyce