The MGB might not be the fastest classic car in the world. It might not be the prettiest, either. Or the most economical, the best handling, the most rewarding to drive, or the cheapest to run.

It is, however, the easiest classic car in the world to own. Nothing else comes close. As a result the MGB is perhaps the one that more people aspire to that any other, absolutely nailing the sweet spot between desirability and affordability. So let’s take a look at what makes it so special…

Launched in 1962 as a replacement for the adorable MGA, the MGB spanned three decades and over half-a-million units before it was dragged around the back of the factory and put out of its misery with a well-placed bullet: by that time it had done an Elvis and become a shadow of the lithe and handsome car that everyone had fallen for almost two decades previously.

But we are getting ahead of ourselves.

A New MG

On paper things didn’t look promising, back in the day: the B-series engine that was fitted to the then-new MGB (and stayed fitted throughout its entire life…) might have been bored out to 1.8-litres but its origins could be traced directly back to the dark years immediately following World War Two, while suspension and brakes were themselves taken wholesale from the outgoing MGA, which was hardly a paragon of cutting-edge engineering. A degree of modernity might have been conferred by the use of a new-fangled monocoque body but make no mistake; this was evolution, not revolution.

But the world loved it. The engine might have been ancient but it cranked out a lively 95bhp, endowing the MGB with a 0-60mph time of just over 11 seconds. Not fast now but back then it must have felt amazing, especially with the roof down and your ears ringing with Love Me Do by The Beatles, that new Liverpudlian band that everyone was talking about.

Even contemporary road tests observe that the early cars were basic; a heater was an optional extra, as were wire wheels, Dunlop tyres, and an overdrive. They also remarked on the car’s enormous steering wheel, necessary because the steering was so heavy at low speed, and its wooden brakes. But none of that mattered because the MGB wasn’t really about driving. It was mainly about sex.

Sex is something the Brits hadn’t been very good at until then, but the guys and gals from Abingdon couldn’t have done a better job if they’d been force fed Viagra and forced to work to a backbeat of John Holmes grunting.

We might have been a bit slow on the uptake but once we’d discovered sex we were the world epicenter of the bonking industry, and the MGB – along with the E-Type and Mini – was our weapon of choice. ‘Safety fast’ was dead, replaced by slogans like ‘You can do it in an MGB’ at the bottom of a photograph of a beautiful woman leaning on an MGB, a suggestive smile playing on her lips…

Not Just a Convertible

The convertible MGB was joined by the MGB GT in 1965, a fixed-head coupe with a hatchback boot and two tiny rear seats, opening the car to the family man and woman.

It too, was an instant success bringing four seats to the car in which your children may well have been conceived. It was, perhaps for the first time, possible to have children and still be seen as young and sexy: your dad might have piloted a sedate, upright, three-box saloon with a pipe clamped firmly between his teeth and a home-kitted cardigan to ward off the chill, but you could demonstrate your virility for the whole world to see. Family cars were now sexy and sporty.

Four on the Floor and Six Under the Bonnet

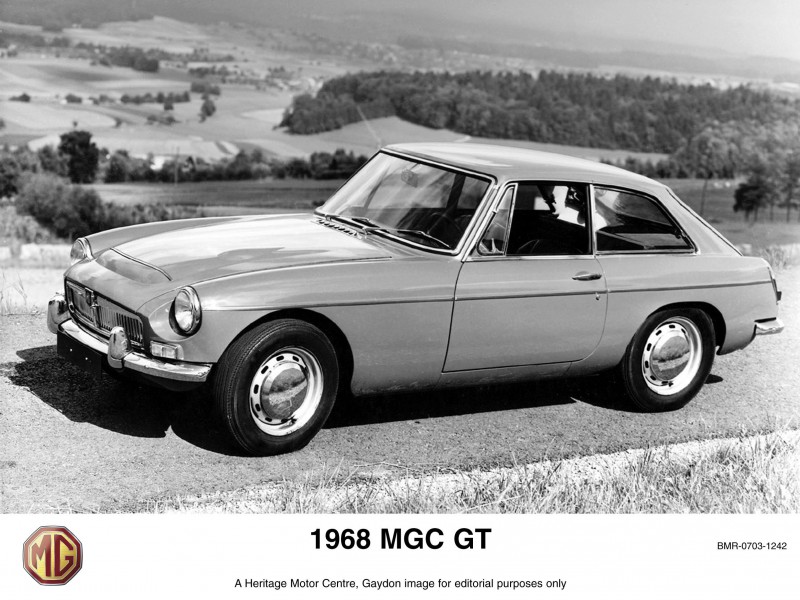

With a three-litre straight six under the bonnet, the MGC was meant to be a replacement for the Austin-Healey 3000. With a heady 145bhp and only a simple bonnet bulge to distinguish it from its smaller brother, the MGC should have been a raging success. After all, a top speed of 120mph was properly quick and buyers could choose from a coupe or convertible, and a manual or an automatic, making it the perfect choice for anyone who wanted something small, fast and nimble.

However, despite different suspension and steering settings to accommodate an engine that was just over 200lbs heaver than the four-cylinder B-series, it didn’t handle that well and received a lukewarm reception from the world’s press. As a result, sales were poor and it lasted just two years, being taken out of production in 1969.

Those damned Yanks – and that bloody Costello

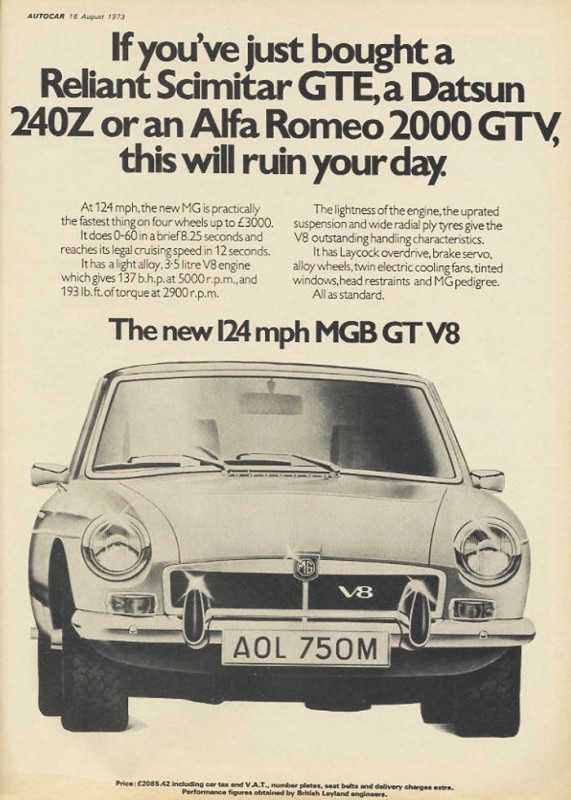

For some people a lowly four-cylinder jobbie was never going to be enough, not now the MGC had showed that more performance was possible and the Buick V8 had made its way across the water and was sitting prettily in the Rover P5B. So BL popped one under the bonnet of the MGB GT to create the MGB GT V8.

Well, it did but only after the Costello MGB V8 of 1971 showed that there was a market for a V8-powered sportscar. The engine Costello used was tuned to produce around 160bhp, creating a car that could reach 60mph in under eight seconds and go on to a top speed of around 130mph.

BL, late to the party by two years, then royally cocked it up by only offering 130bhp in the MBG GT as Rover would only let MG use the low compression version of the V8 engine in case it cannibalised sales (however a couple of ‘factory’ high compression MGB V8s do exist like this one on Patina), denying customers the soft-top that Costello offered. This one lasted three years, killed off in 1976 not by poor handling (it handled very well as the V8 engine was actually lighter than the four-cylinder) but its poor fuel consumption. Twenty miles per gallon wasn’t too bad, but these were the days of fuel hysteria and gas-guzzlers were unacceptable, politically and financially.

Eighteen years, but not the same eighteen

The MGB changed a little, and a lot, over the years. While the standard bodyshell and interior stayed broadly similar, it did receive a few minor, and one major, change throughout its life.

The Mark II was introduced in 1969 with a slightly different manual gearbox. An automatic gearbox was also available for the first time. It also gained an alternator to replace the dynamo, and became negative earth.

The Mark III of 1973 brought a new dashboard and interior, while legislative changes in the US market led to the infamous rubber bumpers and raised ride height that purists claim ruined the car’s handling and looks.

Driving

With rack-and-pinion steering, a low centre of gravity, and almost 100bhp to play with the MGB was a revelation back in the early sixties. It sounded nice too and was low-geared enough to give pretty decent acceleration, especially through the gears, which is where it counts. So, with the wind blowing through your hair it must have been a lovely place to be.

It still is. Of course, the MX-5 is much better but then it is thirty years newer. So you have to approach the MGB with the right frame of mind, which just means a willingness to have fun at much lower speeds than you are used to – and at that, it excels. It feels a bit vintage, a bit crude but then you realise that you’re smiling as you travel at 40mph.

Gearshifts are deliberate but can be made in a very satisfactory fashion with a well-timed flick of the wrist. The brakes might feel a bit dead but they do the job well enough, as does the suspension, which is a bit roly-poly but is soft enough to let you explore the effects of weight transfer on the handling.

It’s a lovely old bus, but if lovely old bus isn’t your thing, then no car can be inexpensively tuned like the MGB.

What to Look For

It’s a BL car from the sixties and seventies, so what do you think you’re looking for? Yes, rust. It wasn’t unusual for cars to suffer from catastrophic rust within five years back then; dial in some of the worst quality control in the industry, and you’ll understand that few, if any, cars now exist in unrestored form.

This introduces its own quality control issues: if the restoration has been done properly then someone else has taken the financial hit, leaving you free to enjoy years of cheap motoring behind the wheel of a peerless example of British engineering. But, if they’ve done it badly (and there are plenty for whom a tub of P38 and a can of Halfords’ paint constitutes a restoration), you are entering a world of hurt.

So you need to look past the shiny paint and immaculate interior (trim and seats are cheap to buy and easy to fit, giving even the rattiest example a credibility it doesn’t deserve) and prod and probe with a screwdriver and a magnet. Use a torch to examine every square inch of the underside and lift carpets and door trim to get a good look into the sort of places that a bodger would ignore, including the bulkhead behind the dash. Door fit is a good guide to serious, structural rust and opening one and trying to lift it on its hinges will show up anything nasty lurking in the door pillar.

You don’t need to worry about the mechanical bits because they’re all cheap to buy, easy to fit, and offer a world of modification that won’t harm the resale value one iota. In fact, given that there are few nicer ways to spend money than by buying an upgraded part because the old one is FUBAR, it might even make sense to buy a sound, but tired, example and upgrade the stuff that’s important to you.

New and Improved

Speaking of which, one of the many joys of owning an MGB is that no other car offers the same range of tuning bits to develop and improve the car to better serve your needs.

The B-series engine is simple enough that you can work on it yourself or, if you really go to town – something that is ridiculously easy to do – you can send it away to be modified by any number of specialists, with the subsequent power limited only by your wallet…

The same holds true for the brakes, suspension, and interior. In fact, you could build a brand new car entirely from brand new parts sourced via the Internet. You’d have a whopping credit card bill – but the resulting car would happily be able to keep up with just about anything rolling out of a factory today.

If you really want to go all out, one company, Frontline Developments can restore your MGB to ‘as-new’ with a modern Mazda engine, 6 speed gearbox, air-con, electric windows and the list goes on. 300bhp in an MGB, now you’re talking…

What’s she worth, mister?

Values are almost impossible to accurately nail, as the range of cars out there is impossibly wide. You’ll see one-owner-from-new, reference models going for silly money, and rusty, unfinished projects going for pocket money.

If it were me, I’d hold out for a convertible that’s had a brand-new British Motor Heritage (or similar) bodyshell and decent paint job in the recent past and not worry about anything else. I’d then spend a very happy year and five grand bolting shiny bits to it before driving it to death and smothering it with love. Ten thousand would easily see that project complete, but half would buy a very usable car that’s been cherished by a member of one of the many MGB owners’ clubs.

If you want one to race or hillclimb, then I’d do the same with an MGB GT but there are plenty out there for well under five figures that have had the necessary work done and would be a reasonably cheap turnkey option.

MGC and MGB GT V8s are rarer and much more expensive and don’t necessarily offer anything the four-cylinder cars don’t other than added complexity (well apart from a some wonderful noise and the possibility of a much greater return on your investment)…