The Citroen 2CV is, like the VW Beetle, Porsche 911, and Austin Mini, a car so perfect in its execution that it simply refused to die; despite Citroen’s attempts to modernize it over the years with the Dyane and Ami, the original design was so fit for purpose that tinkering was impossible.

That the 2CV was so right was no coincidence as more than 10,000 potential customers were interviewed in what may well have been the first large-scale consumer clinic run by an automotive maker anywhere in the world. The design brief was straightforward: it needed to be able to carry two men and 50kgs of potatoes or a small barrel of wine in comfort, and consume fewer than 3 litres of petrol per 100kms (78mpg).

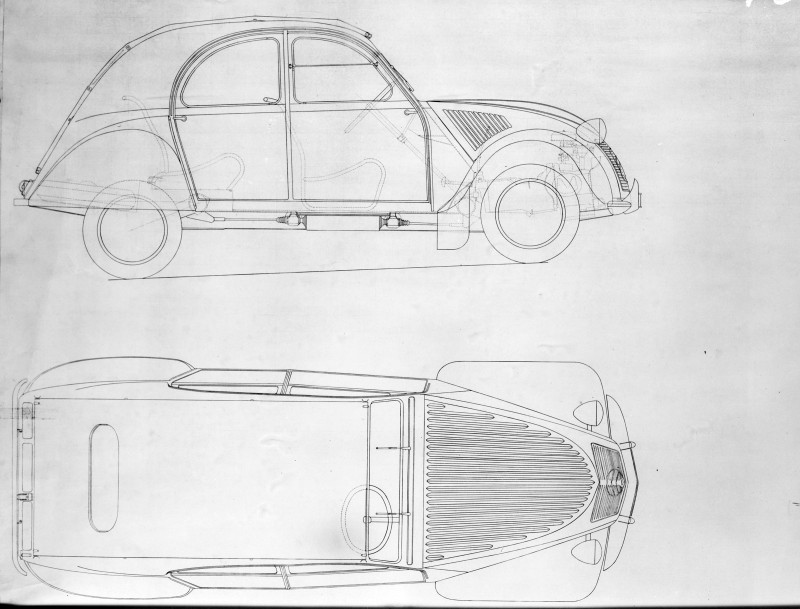

By 1936 the first mock-up was completed but Pierre Boulanger, Citroen’s vice-president and the car’s project head, thought it needed more headroom, eventually insisting that he should be able to wear his hat while driving, an eccentricity that contributed in no small way to the 2CV’s curious profile.

By 1939 the car was almost as we know it now and Boulanger ordered 250 to be built in time for that year’s Paris motor show. In the end just one was completed on time, which wasn’t the disaster it might have been as the Second World War was declared the very next day. Development continued in secret for the next six years and the finished car was first shown in 1948.

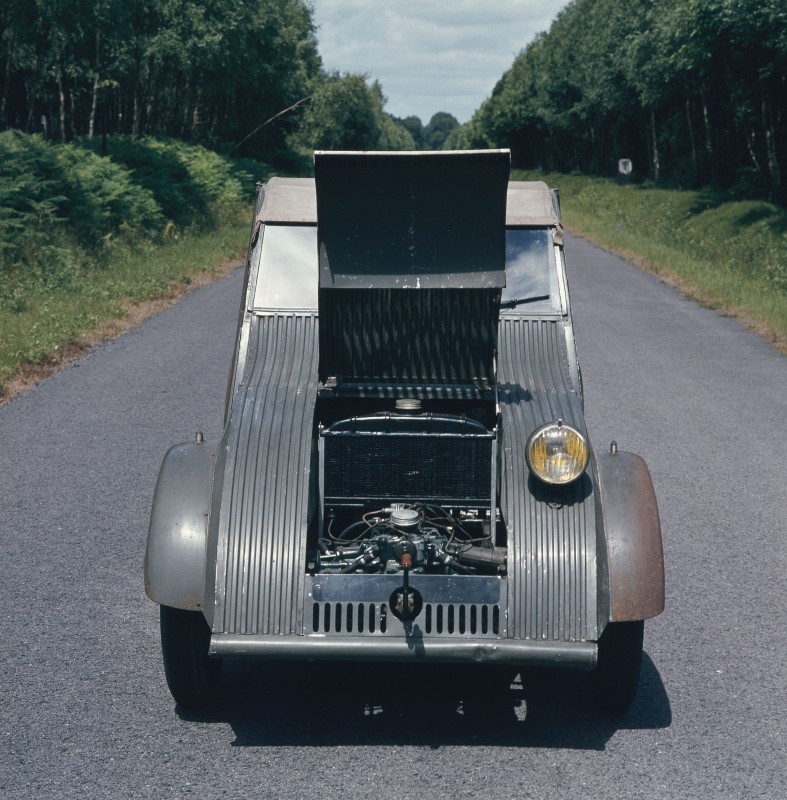

Featuring light-gauge steel (aluminium was considered and rejected in favour of steel, a much cheaper material) and corrugated in places for extra rigidity, it was powered by a 375cc flat-twin, air-cooled engine and an innovative inter-linked suspension that, it was said, enabled the car to be driven up and down a flight of steps in comfort.

The 2CV was eventually unveiled in 1949 and it was an instant success, exploiting a niche that rival car firms hadn’t even realized existed. The little Citroen sold in huge numbers to farmers and city folk alike, appealing to both thanks to its frugality and ability to swallow large loads or four people comfortably, something the full-length fabric sunroof helped enable. Within months there was a three-year waiting list, a backlog that eventually peaked at five years.

It wasn’t perfect, of course. It was only offered in grey at first and only slowly gained creature comforts like door locks and an ignition key. The canvas seats, which resembled deckchairs more than car seats, might have been reasonably comfortable but they weren’t especially supportive on long journeys or round bends. Still, they could be removed for al fresco picnics, a beautiful touch that remains unique, even today.

The 2CV became more powerful over the years, although words like ‘power’ mustn’t be interpreted as meaning that it ever got particularly quick. First upgraded to 425cc and then 435cc, the engine eventually settled at 602cc with a top speed of 71mph, 31mph faster than the original car. The 0-60mph acceleration was equally leisurely, but then speed was never the 2CV’s forte.

The 2CV died in 1990, killed by legislation, not demand.

Driving

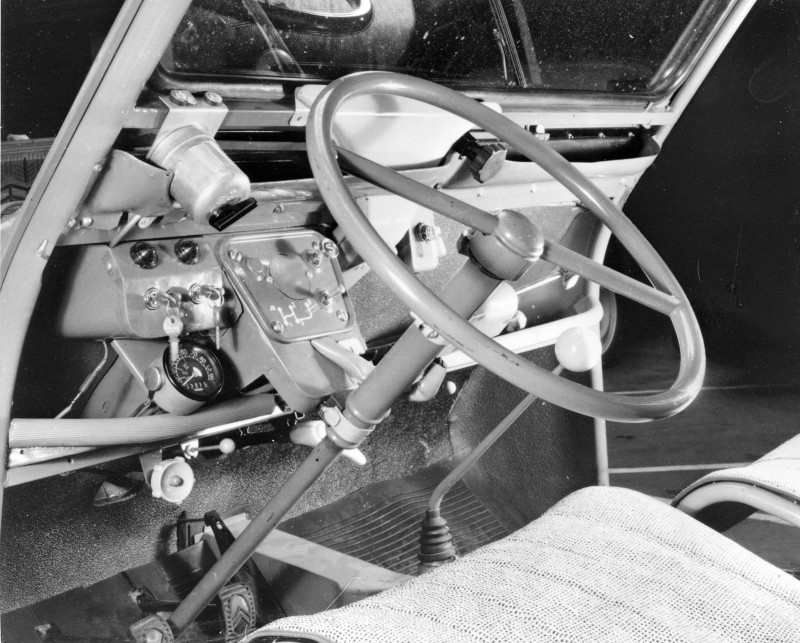

The 2CV is, to modern drivers at least, a bit crude; there is a lot of exposed, albeit painted, metal and the lack of passive safety features worrying yet they retain a huge charm, even today.

Progress is slow at first, but that soft suspension grips and grips, allowing remarkably high speeds to be maintained on even quite twisty roads – providing the driver can resist the urge to slow down when they first experience the car’s often dramatic body roll.

The gear lever can confuse novices too, as it sprouts out of the car’s bulkhead and is of a push-you-pull-me action, but it’s a layout that becomes second nature very quickly. Otherwise it’s pretty standard stuff, with decent brakes and conventional, if sparse, controls.

Derivatives

The 2CV sprouted an unrivalled number of derivatives and ‘improved’ models over the years, although none lasted in quite the same way as the original did.

The 2CV itself was available as a pickup and a van as well as the original saloon. The van, or Fourgonnette, was also available as a ‘Weekend’ special edition, with side windows and collapsible rear seats, allowing a tradesman to use it as a family car at, well, weekends. The pickup was similarly successful, even finding a role with the British Royal Marines as an amphibious, helicopter-portable vehicle, some of which were mounted with recoilless anti-tank guns!

Citroen further exploited the military theme with the four-wheel-drive Sahara.

Fitted with two engines – the normal one drove the front wheels while a second, mounted in the boot, drove the rears – fewer than 700 were built, making it the rarest and most collectable of all of the 2CV derivatives.

In 1961 the Citroen Ami was launched aimed at a more upmarket clientele than the utilitarian 2CV.

Available as a saloon and estate, it was a huge, if not long-lived, success and was for a time the best-selling car in France. In 1973 the 602cc flat twin engine was joined by the flat four engine from the Citroen GS. This boasted 1015cc and 55bhp, making this the fastest member of the 2CV family bar the Wankel-engined prototype that featured a coupe body and a heady top speed of 89mph. (This engine eventually settled in the Citroen GS as the Birotor, but unreliability and thirst killed it despite being super-smooth and surprisingly powerful.

Few survive now as Citroen tried to buy them all back, leaving just a handful in the hands of enthusiastic collectors.)

The Ami was joined in 1967 by the Dyane, a sleeker version of the 2CV with the same mechanical underpinnings but a more modern hatchback body. Citroen had high hopes for the Dyane, even launching a van version called the Acadiane, but it fizzled out in 1982, never having won the hearts of the 2CV enthusiasts it should have appealed to.

The Mehari, a beach buggy-type vehicle, was launched in 1968 and only dropped in 1988, making it the second-longest living variant.

1968 Citroen Méhari. Photo by Giles on Patina.

Designed for, and used almost exclusively by, the military, it had a plastic body and was remarkably effective off road thanks to its light weight (just 570kgs) and long travel suspension.

1968 Citroen Méhari. Photo by Giles on Patina.

And, if that wasn’t enough, Citroen produced a four-wheel-drive version – although sadly with just the one engine this time – for three years from 1980 to 1983.

Running parallel to the Mehari was the FAF (Facile à Fabriquer and Facile à Financer (Easy to Manufacture, Easy to Finance), a weird (even by Citroen’s standards…) utility car designed for use in Third World countries. Launched in 1973 it lasted just six years, finally being withdrawn in 1979 after selling 33,000 examples.

And finally, we can’t forget the British Bijou. Designed and built in Slough, it is a car that, even for a confirmed Citroen lover like me, stretches the bounds of good taste until they snap. Unbelievably, it was designed by Peter Kirwan-Taylor, the same chap who designed the glorious and achingly beautiful Lotus Elite in 1957.

The Bijou might have been a tad faster than the 2CV at the top end thanks to a more slippery shape, but it accelerated more slowly thanks to an increased weight. It was also very expensive, a factor that accounted for very poor sales. Just 207 were made.

Kit Cars

The 2CV, with its ladder chassis, air-cooled engine, and nut-and-bolt simplicity made it an ideal a base for a kit car, something not lost on budding car designers across the globe. Some, like the Lomax 223 or the various Hoffman kits, are well engineered and good-looking but rather too many were ugly and ill conceived. There is a miscellany of ‘Lotus Seven’ imitations for example, that draw more mirth than admiration, although recent eBay prices have at least been appropriately low.

Modifying

The 2CV lends itself to modification from mechanical upgrades like replacing the front drum brakes with discs from a later model all the way to fitting a four-cylinder engine from a Citroen GS or GSA. In fact, performance mods are more common than you might imagine thanks to a very lively racing scene. Yes, you read that right; the 2CV can, and is, raced in everything up to a 24-hour Le Mans-style endurance race. Motor sport doesn’t get any cheaper or more fun than this.

Pricing

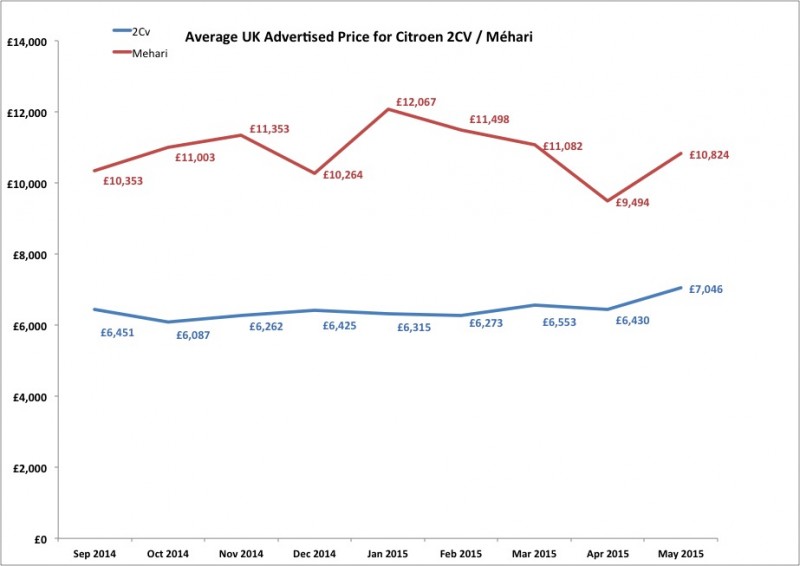

Although prices have risen in recent years (as stocks have depleted), the 2CV is still a (relatively) cheap classic to buy. We have looked at the prices of the basic 2CVs and well as the Méhari:

Although not showing any great gains in recent times, the Citroen 2CV is getting rarer every year (although on any drive through France you can still see them abandoned in farmer’s fields) and this will lead to gentle increases in the future.

What to Look For

Few Citroen 2CVs will have escaped unscathed, so originality – except in the cases of ultra-rare cars like the Sahara – often has to take second place to condition.

Replacement chassis are common and shouldn’t affect the price as long as the work has been done well. Otherwise it’s the usual story; check the paperwork and look for rust.

The 2CV is very simple to work on and most of it is exposed, so seeing any rot should be easy. We’d rather buy a tired car with a solid (preferably new and galvanised) chassis than something that’s shiny but as rotten as a pear.

Having said that, a new chassis won’t break the bank and can be supplied for around £400 and fitted in a couple of long weekends by anyone with a decent socket set.; the 2CV is one of the few cars that makes a Land Rover look complicated…

The rarities, the Saharas, Meharis, and pre-1960 2CVs are really beyond the scope of an article like this, but all should prove a decent long-term investment – if you can find one!

All images (unless otherwise stated are from Citroen UK except Bijou, which is courtesy of Wikipedia Commons