The XKE, or E-type in the UK, contender for most beautiful car in the world

When Jaguar co-founder William Lyons showed up in Geneva in March 1961 with his curvy new XKE sports car, people knew they were looking at an instant classic. Rival automaker Enzo Ferrari went so far as to call it “the most beautiful car ever made.”

Which is funny, considering its designer, Malcolm Sayer, didn’t set out to draft a particularly beautiful car at all, simply an objectively and mathematically aerodynamic one.

The XKE started out as a successor to the XK-SS, the road-going version of the company’s famous D-Type racer. Sayer, using principles picked up in the aviation industry, stretched and shaped the bulbous little D until he’d arrived at the E’s scientifically optimal proportions. They just happened to look great, too.

The XKE didn’t just look fast, though, it really was pretty quick, even if the owner didn’t really fancy himself a hot shoe. Its racing-derived 3.8-litre six-cylinder (enlarged in ’64 to 4.2 litres) put some 265 horsepower to the tarmac and moved the Jag to 100 km/h from a standstill in about 7.0 seconds, and then on up to a top speed of 240 km/h (150 mph).

Car & Driver wrote of the then-new ’61 XKE.Most drivers will be impressed at the way the E-Type enhances their driving. This is not to say that any clod can slip behind the wheel and immediately break lap records, but an enthusiastic, non-racing amateur will find the car greatly extends his capabilities, while those with a definite competition bent will find it a useful, potent road tool.

What really made the car a smash hit, though, was its relative value: buyers could get those stunning looks, that great performance for just $5,670 US (roughly £3,820 GBP) new, equivalent to about $45,000 US (£30,300 GBP) today (at least according to Car & Driver—other magazines quoted as-tested prices considerably lower than that). We should note that for that coin buyers also got power-assisted disk brakes, a four-speed gearbox, leather interior and an aluminum-faced instrument panel.

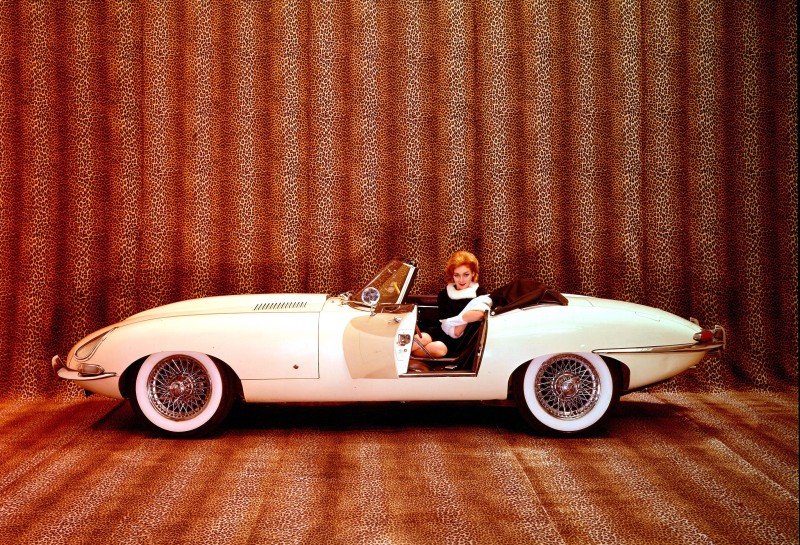

1966 Jaguar E-Type. Photo by vernon on Patina.

XKEs flew out of Jaguar dealer showrooms to the tune of some 15,000 units between ’61 and ’64, but though they easily could have, the company didn’t rest on its laurels. The car went through three generations in its life, which we’ve detailed below.

Three different flavours of XKE

1967-1968 Jaguar XKE Series 1½ Roadster

The first improvements made to the XKE happened in October 1964, and included a larger displacement six-cylinder, beefier disc brakes, and a four-speed transmission with full synchromesh.

Just three years later, in 1967, Jaguar tweaked the first-gen XKE again – to meet new standards mandated by the U.S. government – and while they were at it, started phasing in some second-generation features, creating a transitional “Series 1½” car.

The changes included the removal of the Perspex covers over the headlights; a switch to a two-carburetor Zenith Stromberg setup in place of the more powerful three-SU-carbs arrangement; and the use of hexagonal knockoffs on the wheel centers instead of winged spinners.

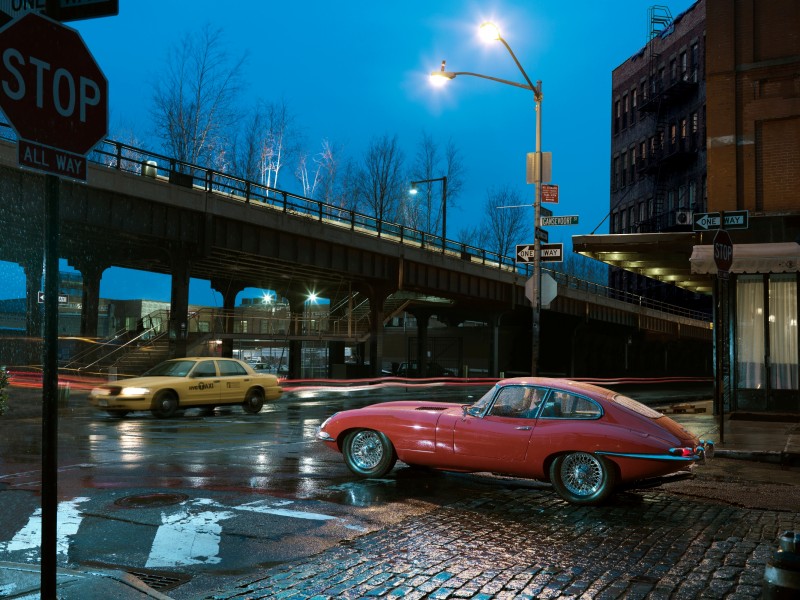

1970 Jaguar E-Type. Photo by wildnick on Patina.

1968-1971 Jaguar XKE Series 2 Fixed-Head Coupe

The Series 2 cars cemented many of the changes seen in the Series 1½ cars: the Perspex headlight covers were gone for good, for example, while the detuned twin-carb engine for U.S.-market cars was there to stay. The rear bumpers grew to wrap around the back of the car, and the taillights moved to a spot just below them. Second-gen XKEs also got wider grille openings for better cooling, plus twin electric fans to boot.

Inside, front seat headrests, mandated by U.S. law, were fitted, as were new, safer rocker switches in place of the old, pointed toggle switches. The dashboard was no longer symmetrical, and the ignition switch previously located there made its way to the collapsible-for-safety steering column.

The Series 2 would be the last generation to see a two-seat fixed-head coupe, which was dropped in 1971 in favour of the longer-wheelbase 2+2 coupe introduced in ’66.

1971-1975 Jaguar XKE Series 3 Coupe 2+2

The biggest change to the XKE lineup’s styling happened in 1966 when Lyons got designer Bob Blake to upset Sayer’s perfect proportions by stretching the car nine inches and reshaping the roof to turn it into a 2+2 that buyers could more easily persuade their spouses was “practical.”

All third-gen cars rode on this longer wheelbase platform, and got a wider track with flared wheel openings, too. The six-cylinder was swapped out in favour of a new 5.3-litre V12 paired to a manual or automatic trans, which didn’t do as much for the performance as you might assume (horsepower saw a slight bump, while top speed and acceleration numbers stayed where they were).

The four-place coupe’s more upright windshield was laid back again in Series 2 and 3 spec, and though this helped make it look a little more sporty, it couldn’t save this generation, and this style, from earning a reputation as one of the lesser desirable XKEs.

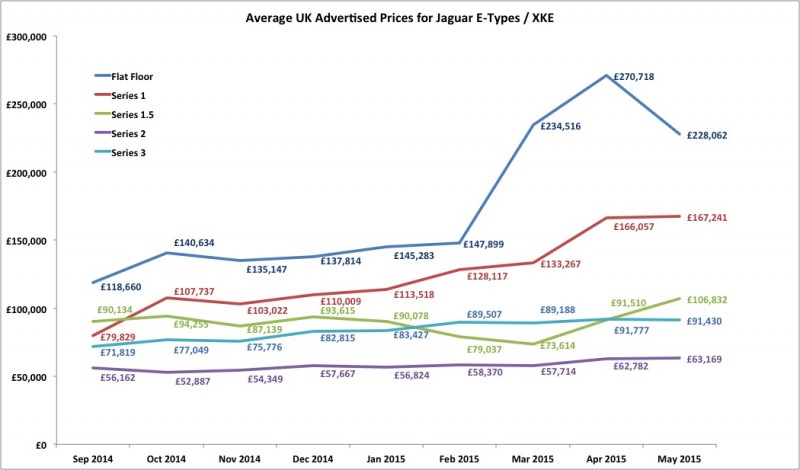

Pricing

As might be expected, pricing for XKEs varies tremendously depending upon the year with early cars fetching a significant premium and later cars being available at under half the price.

Interestingly it is the Series 2 cars that are the cheapest to buy and the very earliest cars carrying a significant premium.

Like old Ferraris and flats in central London, XKEs tend to be a good barometer of the classic car market, therefore it is interesting to see a flattening (and in the case of early cars a correction) of prices. A wider indication of the market as a whole?

Maintaining

Buff books like Car & Driver pegged excessively high oil consumption as a problem early on – something engineers attributed to the engine’s motorsports origins – but generally speaking the six-cylinders are known to be pretty reliable if they haven’t been leaned on too hard. The V12 is supposed to be even better.

The biggest issue with these engines is overheating, so keep an eye on the temperature and pressure gauges, and an ear out for working cooling fans, when running up a prospective buy. Engines in obviously poor shape need not be a turn-off, by the way: there’re plenty of spare parts suppliers around if you’re up for tackling, or financing, a rebuild.

More likely to fail are the things attached to these engines, namely the Lucas electrics: Road & Track surveys early on found owners complaining about the starter, generator and instruments, specifically. Also a known problem from the start: rain leaking through convertible tops.

Prices on XKEs are generally pretty high, and sellers know this, so if the asking sounds too good to be true, that’s because it is. Be vigilant for all sorts of wear issues in cars with suspiciously low asking prices, and check the VIN to make sure your right-hand-drive car didn’t start out as a left-hander, or that your convertible wasn’t born a coupe.

For the Anoraks

If you love trivia as much as we do, you’re going to know a little more about the XKE’s designer, the mysterious Malcolm Sayer. Though it might be just a rumour, it’s alleged he picked up the principles of aerodynamics used to shape the XKE from a German professor at the University of Baghdad shortly after the Second World War.

His colleagues at Jaguar are known to have remarked how Sayer was a perfectionist, capable of engineering mathematically perfect aerodynamic car parts down to the thousandths of an inch.

Former Jaguar worker Mike Kimberley told the BBC for a story on Sayer“[During the XKE’s development,] someone decided the bonnet would look nice with a Jaguar badge on it and he carefully indented it, all 1.5-mm deep, so it was flush and when Malcolm saw he literally took off. He insisted it was removed, because what it was doing in his mind was changing the purity of his calculations.”

It really is marvellous that the XKE, a car that may be the most beautiful ever built, was designed without a thought toward its styling. But maybe that just helps to prove the old adage: that good form follows function.