1996 marked a new era for Lotus, giving volume to what had previously been a relatively small manufacturer; the front-wheel-drive Elan might have been a technological marvel, but it didn’t exactly set the market alight. The Elise did.

Lotus had taken more than 1,300 customer deposits for the Elise by the time the first cars were with their owners, which should have meant that the first three years’ production was completely sold out. But greed took its toll, and the chaps at Hethel decided to up the annual production from 400 units to 2,500, which must have been a nice problem to have, even if it did play havoc with the new model’s perceived exclusivity.

Models

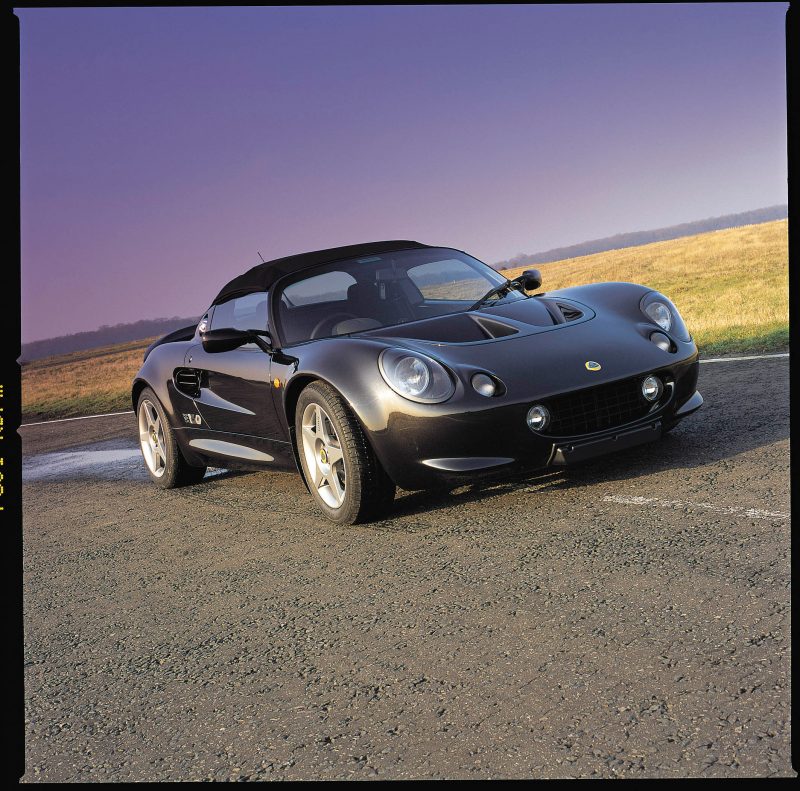

If you’re coming to the Lotus Elise from a more conventional sports car manufacturer, you might initially struggle to get your head around the 1.8-litre engine, which only develops 118bhp. But fear not, because it’s only hauling 723kgs, meaning it has a dragon-slaying 163bhp per tonne, enough for a 0-60mph time of just under six seconds. (Autocar managed an almost unbelievable 5.5 seconds when it was new.) More importantly, they’re viciously quick in the mid-range, with an urgency and throttle adjustability that is just about unique.

This relative lack of outright power is a big part of the Elise philosophy of ‘less is more’. This means there is no power assisted steering, no servo assistance for the brakes, and no electric windows or other unnecessary frippery like carpets.

Or welds. The extruded aluminium chassis was literally glued together, a technological innovation it shared with my Raleigh Dynatech mountain bike of the late eighties. In both cases glue seems to be a perfectly acceptable substitute for the ministrations of the welder’s torch.

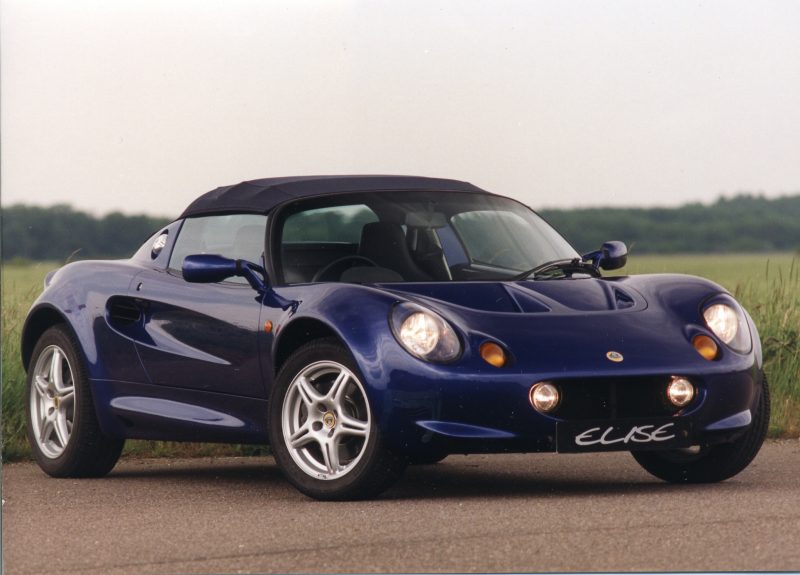

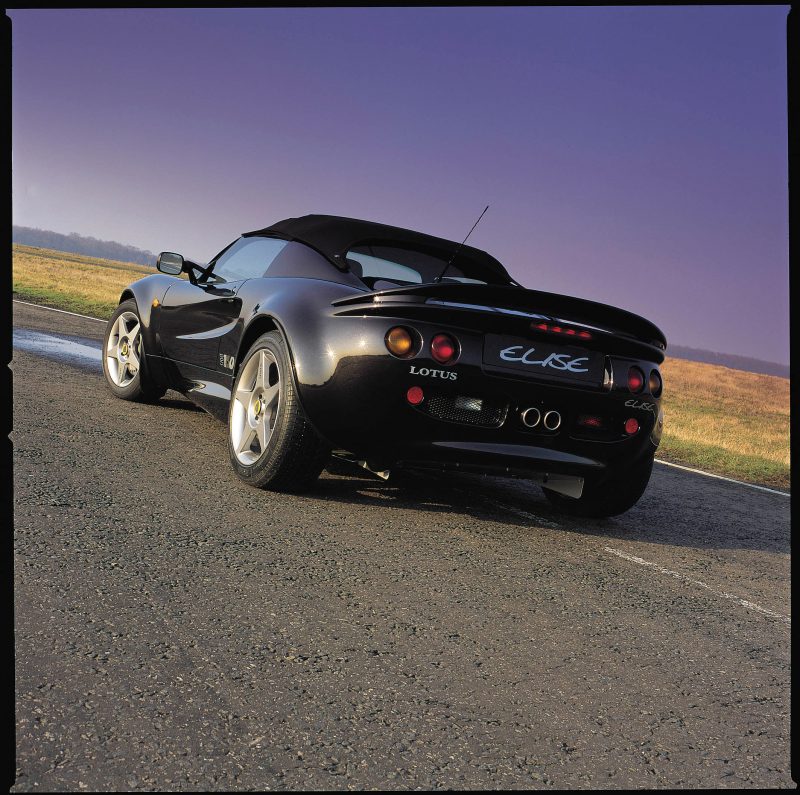

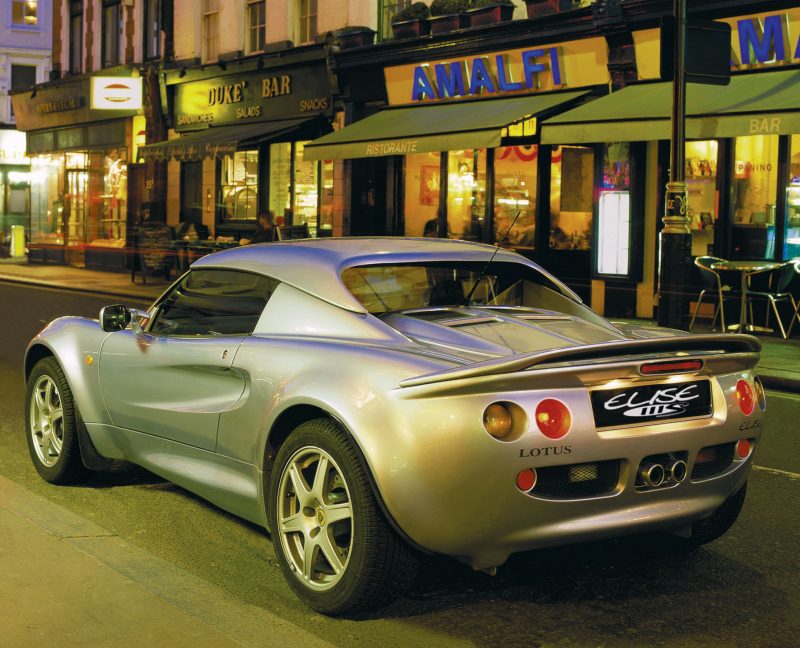

The S1 cars, with the single headlights, are the ones everyone wants. This makes them the one you want too; crowd-sourced data is sometimes wrong, but not in this case. The standard Elise is all the car you really need, but if you fancy something a bit rarer, Lotus brought out a few special editions, starting with the 111S (initially badged as the Sprint), which retained the K-series engine but gained a close-ratio gearbox, with slightly raised first and second gear ratios and a slightly lower fifth. This meant that it was no quicker from a standstill than the standard cars but gained massively in the mid-range; it was a full 5.8 seconds faster to 100mph than the bog-standard 118bhp car, an improvement that had at least as much to do with the gearing as the 143bhp from the VVC K-series engine. The 111S also gained a bit more seat padding compared to the standard Elise plus headlamp fairings, cross-drilled brake discs, a rear spoiler, and six-spoke alloy wheels.

The Sport 190 with 187bhp (190PS) arrived in 1997. The extra power – and it was a LOT of extra power – made itself felt by way of an earth-shattering 4.4 0-60mph time and mid-range overtaking to match. The Sport 135 came along shortly thereafter in 1998 with 145bhp (I know…), with the Sport 160 coming along in 2000. The rarest of them all is the Sport 135 with just 50 examples ever made.

Fancy-pants editions included the green and gold 50th Anniversary Edition and two wonderfully politically incorrect tobacco-brand, F1-inspired editions: the utterly gorgeous red and white Type 49 ‘Gold Leaf’ edition and the Type 79 in black and gold JPS-livery. In these days of hidden cigarette packets and anodyne packaging both hark back to a more sensible time when racing was dangerous, sex was safe, and your pre-race warm-up involved smoking a couple of tabs while performing press-ups on top of someone else’s wife. For that reason, if no other, these are the two models you should buy.

Unless you can find a MMC-equipped car. The very early cars were fitted with MMC, or metal matrix composite, brake discs front and rear. They are very, very light compared to the steel discs we’re all more used to, with owners claiming that you can hang all four MMC discs comfortably off one finger. They also wear well, but are hugely expensive to replace when they do finally give up the ghost. Finding a pair is going to be your first problem, and by the time you do manage to track a set down you’ll be begging the owner to sell them to you, even at £250 for a pair of used examples.

The pretty little S1 was replaced with the almost-as-pretty S2 in 2001.

Driving

At 6’4” I’m almost too tall to drive an Elise. As it is, I simply can’t squeeze into one if the roof is up. With it furled, it’s almost a doddle to slide into the driver’s seat, and an absolute doddle if the car is fitted with a removable steering wheel. (Which is also a bloody good anti-theft measure.) Once in, I feel a bit like Big Ears trying to make off with Noddy’s car, but who cares what anyone else thinks when it feels this good?

Folk talk about the immediacy of the Elise, a cliché that is, like almost every other cliché, true. There is none of the artificial, electrically induced dartiness of a modern bloated carp like the MINI. No, what nimbleness and litheness there is, is the result of an absence of mass and clever engineering. Colin Chapman would have approved of the Elise, which is not necessarily something you can say of the M100 Elan.

Performance in the Elise is more about maintaining momentum and corner exit speed rather than bludgeoning the Laws of Physics in a vulgar display of cheap horsepower and too-wide tyres. If you’ve driven a 2CV you’ll understand; this is a car that flatters a good driver and punishes a bad one; lift off mid-bend and it’ll sling you into the hedge faster than you can soil your pants. But when you get it right the rewards are enormous; few cars are as faithful as the Elise as it slinks through bends in a stunning display of telekinesis.

On the subject of performance, the Elise makes a strong case as being essentially a single-seater: a 75kg driver drops the power-to-weight ratio to 148bhp per tonne, while adding another 60kg drops it to a pedestrian 137. As a result, no keen Elise owner is going to sully the power-to-weight ratio with anything as frivolous as a passenger.

So, if you are thinking of buying an Elise you need to be sure you are the sort of person who is comfortable with their own company. Oh, and the elements, because both the soft and hard-top leak like a sieve, so you’re going to be sitting in a pool of rainwater after even the gentlest of showers. An Elise is what blokes like Ranulph Fiennes drive when they feel the need to man up after realising that their everyday-driver Defender has turned them into a bit of a softie.

Buying one

The K-series engine comes from the MGF, so it’s prone to overheating and blowing the head gasket thanks to marginal cooling. If it is going to shit its pants then it’s probably done so by now – and if it’s been repaired properly then your woes are over.

Other than that, there is little to worry about; the K-series might have a poor reputation but the reality is that it’s a sturdy little thing if it’s been serviced by someone who knows what they’re doing, and one advantage of rising prices is that people aren’t afraid to lavish a bit of love and money on them now.

The car’s light weight gives the transmission, suspension, and brakes an easy time too, and I’d be more worried about an ultra-low mileage garage queen than I would about an enthusiast-owned car that had been lightly modified and occasionally allowed to stretch its legs on a track.

Having said that, corrosion can be a problem in higher mileage cars as the aluminium chassis corrodes around the top of the front suspension upper wishbone. The problem is the steel shims and bobbins react with the aluminium chassis, a bi-metallic chemical reaction that will be familiar to Land Rover owners of all vintages. If it’s caught early it can be halted but it is something to look for, although the chaps at Lakeside Engineering suggest that only high-mileage cars are likely to have suffered perforation; lower-mileage cars should just need preventative, rather than remedial, work. The front floor pans can corrode too if water has been trapped under the mats. Lotus used to glue another section of aluminium over the top to ‘fix’ the problem; others have alternative, and possibly better, solutions.

The third significant chassis problem is the suspension mounting points. They’re glued and riveted on but even a middling accident will rip them off, and they’re impossible to reattach. The fourth area to look at is the rear subframe, which is the only bit of the chassis to be made of steel. Replacing it is a bit of a faff but as the subframe itself is only £500, a rotten one is probably a bargaining chip rather than a reason to walk away.

Unlike the final chassis problem, which is accident damage. Luckily, it’s easy to spot given the stripped-down nature of the car; if you see ripples in the floor or any other untoward angle in the extruded aluminium sections then it’s time to walk away as the cost of a new chassis will far outweigh the value of the car.

You can reasonably expect all five gears to engage smoothly, although a heavy clutch pedal isn’t unheard of, and if the suspension does anything other than reduce you to tears of joy on the test drive, it probably needs work. The ball joints are seen as consumable items and need replacing every 35,000 miles. They, like everything else on the Elise’s suspension, are commonly available and easily bolted on; it’s setting the geometry that takes the time and you’d be well-advised to get it done by a specialist like center gravity.

There is bugger all to the interior, so it shouldn’t take long to check. A noise from the Stack rev-counter is just the stepper motor, an annoying but ultimately unproblematic fault. The seat bolsters wear and the switchgear is from Peugeot so you can expect the odd electrical SNAFU, but otherwise it’s all good inside with the exception of the windows, which tend to stick in their frames, and repairing it is a big job as the two halves of the door are bonded together; if your car-obsessed best mate is a gynaecologist or a vet he might be able to fix it for you cheaply but everyone else is going to be stuck with a large bill so do check to make sure they wind up and down smoothly.

The glassfibre body shows all of its ills quite openly but it’s still worth taking the time to go over every single inch of it to check there are no cracks, scratches, badly repaired accident damage, or stress fractures developing. The low ride height also means that the front clamshell is prone to speedbump damage.

What to pay

Around 8,600 standard S1 Elise were made, and while a fair few of them will have been stuffed into a ditch at some point in their lives, the majority of them are still on the road and being touted as the Next Big Thing.

So, you’ve missed the sub-£10,000 cars already. Decent cars now start at £12,000, with good ones going for £15,000. This still seems like a bit of a bargain to us, and they’re currently showing an annual growth rate of around 5%, which is better than money in the bank. (Please feel free to use me as a reference if your significant other needs persuading; if they’re daft enough to listen to anything I say then they deserve everything they get.)

Left-field alternatives

The S2 Elise is only marginally heavier and a fair bit less spiky at the limit; they are *whisper* a better car for the majority of drivers, but everyone will think you’re a wimp if you buy one.

Ditto the Vauxhall VX220. It’s bigger (which is handy if you’re anything other than jockey-sized), cheaper to buy and run. But it’s a Vauxhall. ‘Nuff said?

Of course not. The VX220 is a way better car, and one that proves that image is everything; if it wasn’t, we’d all be talking up the prices of the Vauxhall and rubbishing the Elise for being too small and tricky.

Modifications

Few cars lend themselves to being modified like the Elise. In fact, your biggest problem when you’re trying to find one will be to find one that has received the very minimum of modifications.

All we would say here is that originality and provenance are the keys to maximizing your car’s value in the long-term, so a slow but steady progression back to standard specification will pay dividends, but if you can’t resist the urge to prove you know better than Lotus’ engineers then at least make all your modifications easily reversible and keep the bits you take off.

Carlton Boyce