Tata has finally said ta-ta to the Land Rover Defender, the British icon killed off by European bureaucrats in a fit of consumerist piqué that also banned the sale of straight bananas and eggs by the dozen. The doughty Brit died, not because no one wanted to buy it anymore, but because it was too dirty to meet forthcoming European Standards on vehicle emissions.

Bastards.

Wait, hang on; have you ever driven a Defender? You have? In that case you’ll also see the death of the archetypal four-wheel-drive as a long overdue mercy killing; the Defender clung on to life for far too long when, despite being the automotive equivalent of the cantankerous uncle who spends his days farting and complaining about bloody foreigners, it should have been taken outside and shot years ago: I bought a three-year-old 110 TD5 in a previous life that later drew a comment from the MOT tester to the effect that the bulkhead was rotten. That’s structural rot in a four-year-old car that cost me well over £20,000. In the 21st century.

Bastards.

But I accept that I may well be in a minority (although every farmer I know has traded in their Land Rover for a reliable, comfortable Japanese 4x4s that doesn’t force the driver to keep the window open to generate enough elbow room to be able to steer the bloody thing), so here’s a quick run-down for those of you who can’t bear to think of life without a slow, rusty, crude, and hopelessly outdated Jeep-rip-off in your life.

Born in 1990, not 1948

The Defender was born in 1990 when the Defender name was added, turning the Land Rover One Ten and Land Rover 90 into the Defender 110 and 90. (The numbers refer to the wheelbase in inches, a piece of imperial nonsense that must delight Americans.) The actual vehicles stayed much the same as those launched in 1983, which meant asthmatic engines but coil springs and sufficient axle articulation to make them almost unstoppable, which seems to be their main selling point alongside the 3.5t towing capacity.

They also used to be a cheap way of shifting stuff across rough terrain, but given that the last run-out models were selling for north of £60,000, even that doesn’t hold true anymore. Still, they do look tough and so appeal to the sort of Ranulph Fiennes wannabe who wants to rough it while still having his hipster beard ruffled by air-conditioning. (That the air-con system in the Defender is largely ineffectual is actually seen as a positive attribute by many owners as it is so gentle that it doesn’t ruffle their carefully coiffured facial hair; the soft wafts of luke-warm air merely served to perfume the cabin with the scent of mango beard oil, providing a floral counterpoint to the smell of skinny soya lattes that hang on their breath.)

Anyway, my point is that it isn’t an old car that’s survived in its original form for three generations. This is a car that was designed in the mid-1980s, yet was hopelessly outdated even when it was new.

Made, not bought

The Defender is infinitely repairable using nothing more complex than a hammer and an adjustable spanner. Which is just as well, because you’ll be doing a lot of it. Even Defender owners, generally the most forgiving and supportive drivers in the world, are forced to admit that the build quality is appalling, the engineering disgracefully crude and the time spent repairing them can easily exceed the time you spend actually driving it.

This is a relief of sorts because at least you are limiting your family’s exposure to a car that has such poor primary and secondary safety features that it was never tested by Euro NCAP. (Submitting a car for review by them is entirely voluntary but there is probably only one reason why a manufacturer wouldn’t do it, isn’t there?)

Not that anyone can ever accuse Land Rover of dishonesty: under the Safety & Security section of the Defender website, it simply states: “Perimetric alarm with engine immobilisation“. (Actually, it doesn’t. Land Rover can’t even be bothered to spell-check the description, leaving it as “immoblisation”…)

If you are driving a Defender with your family on board and suspect that you are about to have a collision, I’d suggest you quickly stuff each child in their own metal oil drum, cushioning them with a variety of carving knives, running chainsaws and freshly sharpened chisels before jettisoning them out of the back door into the face of oncoming traffic. Thus positioned, they will still be safer than if they had remained restrained in the laughably primitive environment that Land Rover claims is a “robust and comfortable interior”.

What’s it like to drive?

It’s horrible. What Car gave the Defender a one-star review, saying that it is “has vague handling and a horrible ride. The driving position is cramped and the cabin is noisy“, before going on to note that of the many variants on offer “every one of them is complete rubbish.”

CAR magazine was less harsh, awarding it a three-star review in 2016 in a slightly giddy, last-of-the-run review. However, even it had to admit [by] “Any objective measurement of the Defender’s skills will reveal shortcomings in so many areas. Newer cars have come along and surpassed it in so many areas that you might wonder why Land Rover didn’t scrap it sooner.”

My introduction to the marque was as a child, when my father would let me drive the firm’s 101 Forward Control and series 2a 88”. As an eight-year-old I was more concerned with being able to reach the pedals than with NVH and understeer. As a twelve-year-old I graduated to solo off-roading in a series 3 109” and was – again – more interested in clambering over (and sometimes through) obstacles than evaluating it against its peers. As a thirty-year-old I bought a series 2a in a misguided fit of nostalgia and was genuinely shocked to find that it drove like a tractor. I shouldn’t have been, as that is essentially exactly what it is.

A Defender, on the other hand, is more regal, more composed and more refined but only just. Anyone expecting Japanese levels of road holding, comfort and refinement will be sorely disappointed. The on-road experience is noisy, vague and woefully underpowered, even in the later Puma engined cars. The gear selection is vague, the brakes marginal, the noise levels high, and the equipment levels low. It’ll leak, rust, corrode, and break down. The fit-and-finish of the body panels will leave the average under-the-arches cut’n’shut merchant shaking his head in disbelief, and Dulux appears to be the paint supplier.

Yet you can forgive a Defender anything once you are in the rough-and-tumble of the off-road environment. That gutless engine is, you discover, torque-rich and the long-travel accelerator pedal is perfectly engineered to allow you to dribble in the power, one lb/ft at a time. The coil-sprung suspension, hopelessly soft and almost undamped in long high-speed bends, is unsurpassed in its ability to keep rubber in contact with terra not-very-firma.

The elephant in the room for anyone who is tall, or more suited to rugby than football in build, is the driving position, which is cramped and borderline dangerous. Mud rails will give you a tad more legroom in everything other than the pickup, and a smaller steering wheel will also help but you might just have to resign yourself to looking like a gorilla on a monkey bike when you are driving it. Still, it could be worse; you should see how daft I look in a Suzuki Jimny.

But, comfort aside, the Defender is the very best there is at what it does. When you absolutely, positively got to get every poor sod in the car to their destination – no matter how extreme or remote – accept no substitute.

And yet, despite all this, you still want one, don’t you?

Yep, me too. By any objective measure the Defender is a slow, dangerous, environmentally disastrous anachronism that has no place in any rational person’s garage. My old Mitsubishi L200 was more comfortable, more reliable, nicer to drive, and just as practical as my Defender but I don’t find myself scanning eBay for another. Old Land Rovers have a habit of worming their way into your affections in the same way as your old girlfriend, the one with the tattoos and flexible moral code that your mother hated but you remember with a warped affection and an involuntary flinch.

So I’m not going to judge you, even though we both know that it’s going to end in tears; if a friend is someone who turns up at court with your bail money, I’m the best friend who’s standing there in the dock alongside you.

The engines

Look, it’s a Defender, so none of them is going to give you performance or economy that is even remotely like you are used to getting from a properly engineered car that the manufacturer actually liked. Harsh? Not really. I had dinner with a couple of Land Rover engineers once, who told me that the company had no incentive to spend money on improving and updating it as it was selling very well despite all its faults. (Or ‘quirks’, as owners prefer to call them.)

So, the V8 petrol engine is slow and thirsty but makes a glorious noise, while the 200TDI and 300TDI diesel engines are even slower but marginally more economical: expect 20-30mpg in day-to-day use, against 10-15mpg from the V8.

The TD5 engine is smoother and more powerful, and the 2007-onwards ‘Puma’ diesel engines are slightly more sophisticated, but only slightly; Brunel would still recognise the majority of the components, even if the electronics do add an unnecessary level of complexity.

My advice is to buy a petrol-engined Defender as you’re going to be doing low miles. The noise is fabulous, the fuel consumption isn’t ruinously worse than the diesel over such a limited mileage and the options for tuning are limitless. You will also be able to buy a better vehicle for your money as the market for them is smaller.

If you’re going to be using it a lot then the 200 or 300TDI engines are simple, straightforward to work on and decently reliable. A half-trained chimpanzee can repair them and the fuel consumption isn’t much worse than that of the newer diesel engines.

Body styles

You can choose from a pick-up, van or station wagon as standard but if you want one with a crane, extending platform, tipper body or mobile workshop then you should be able to find one without too much trouble because the Defender is, no matter what its foibles, a supremely practical and adaptable vehicle.

As for lengths, the 90 is brilliant off-road, but just too small to be anything other than a plaything. The 130 is enormous but uber-useful, even if it is too big for most UK car-parks. The 110 is a decent compromise between the two but as my farmer brother-in-law once said: a 100-inch high-capacity pick-up with a touch more legroom in the cab remains the Holy Grail that was never offered.

Ex-military Defenders

If you thought that the standard Defender was basic you’ve obviously never sat inside a military version. When you spend your days trying to kill people with bullets, bombs, and depleted uranium warheads you aren’t going to be too worried about whether you’re sitting on vinyl or leather, are you?

So ex-military Defenders are stripped-to-the-bone rudimentary (even the headlamp bezels will have been removed) but they are likely to be have been serviced to within an inch of their lives given that real, human lives have depended on them working properly under every conceivable environmental condition. If you’re a function-over-form kind of person, then this sort of thing might just be up your (civvie) street.

What to look for

Look, it’s an old British car, so you know you’ve got to look for rust, don’t you? And while the bodywork might be alloy, it still corrodes (only the Brits could build an alloy-bodied car that corrodes…), especially where it comes into contact with steel.

Having said that, with enough time and money anything can be restored, so don’t let a scruffy Defender put you off; if the price is right you can buy anything you need to repair and restore it to a better-than-new finish. Fitting is usually a doddle too, as long as you don’t mind buying WD40 in industrial quantities and have access to a small blowtorch for freeing off rusty fasteners.

Few owners worry too much about the odd dent or ding either, which is very liberating. Few cars look as indomitable as a battle-scarred Landie, especially one with all-terrain or, even better, mud-terrain tyres.

The fix-it list

Pretty much every Land Rover Defender you buy will need a bloody good service (all the fluids, including axles and transfer gearbox, need changing and changing frequently) before you do anything else. I’d also budget for new springs and dampers plus Polybushes; the resulting suspension refresh will transform the way it handles, and decent discs and pads will ensure that it actually stops when you want it to.

The wishlist

The wish list will usually comprise bigger wheels and tyres, a winch and some spotlights.

I’d skip the wheels and tyres for now as they only make a bad car even worse to drive thanks to all that extra weight – and anyway, skinny tyres (and since when did 205-section tyres count as skinny?) cut through the mud better than fat ones, which are better suited to sand and desert use.

A winch is pretty pointless, too. You should be off-roading in convoy, so there should always be someone to pull you out.

No, I’d spend the winch money on decent tyres and some tuition first.

The spotlights are a great idea though, as the standard lights are as hopeless as the driving position. LEDs are the way to go, being cheaper, lighter, smaller, more energy efficient, easier to fit, and brighter than the old halogen bulb variety.

As an investment

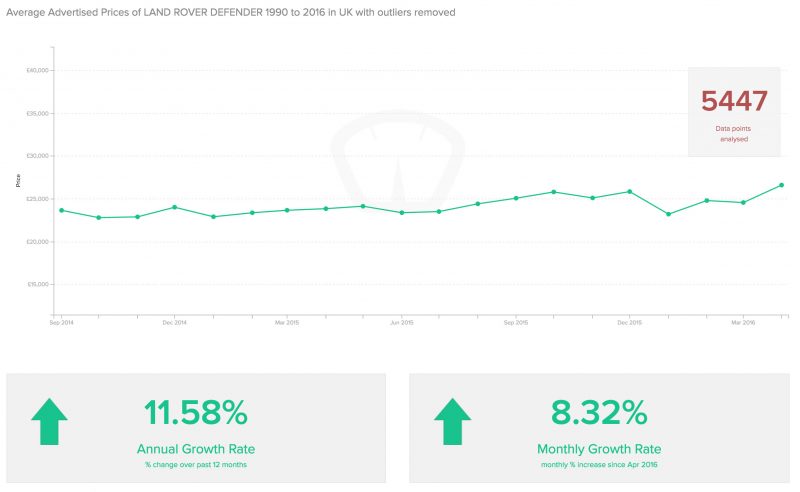

Of course, you could buy a pampered Defender as an investment. Who else can point to a car that was built in the hundreds of thousands, had over a 25 year lifespan and still is appreciating across the board?

(Data from Patin Price Trends)

The limited runs tend to do well, and a Tomb Raider or a 50th V8 petrol will always return strong money. The Camel and G4 Challenge Defenders have a cult-like status among Land Rover fans and perform as well as they look.

The very strongest money is likely to be reserved for the three final edition versions: while £62,000 is a ridiculous sum to pay for a Defender, Land Rover sold out of them very quickly, which must prove something. If you really must invest in one then one of the final three – Heritage, Adventure or Autobiography – cocooned in a Cair-O-Port for twenty years should do the trick.

Or, you could do the sensible thing and buy a sound but scruffy Defender, cherish and love it, refurbishing it as-and-when finances allow. It’ll treat you well and become a treasured member of the family. And when you come to sell it won’t have lost a penny, unlike its pesky Japanese competitors…

Carlton Boyce